“The Perks of Being a Wallflower” – Interview with Stephen Chbosky

by Sara Michelle Fetters - September 21st, 2012 - Interviews

First Kisses are Always Interesting

Stephen Chbosky on the Perks of adapting his acclaimed novel for the screen

Published in 1999, Stephen Chbosky’s The Perks of Being a Wallflower was an instant sensation, becoming a New York Times bestseller with almost a million copies being sold in the United States in the 13 years since its release. But when it came time to transform the book into a motion picture, the author wasn’t going rush things. Chbosky also knew that he had to be the one calling the shots, the story too close to his heart to allow another to adapt the screenplay or direct the film itself.

“No, no one else was going to direct this film,” the author-turned=filmmaker laughs. “I was either going to make this film or it wasn’t going to exist. No one else was going to do it.

“Listen, I think others could have made very beautiful versions of Perks, and there is an alternate universe I almost wish existed where a German film company wanted to make a German version of the novel, and I’d kill to see that movie. But in the end, I just don’t think it would have been right for someone else to have made this movie. It wouldn’t have been authentic. You can’t outsource the adoption of your baby and expect it to have the same sense of history as if you raised it yourself. It’s just the way it is.”

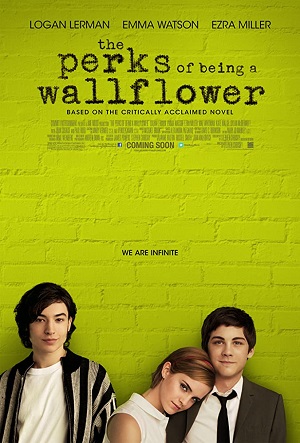

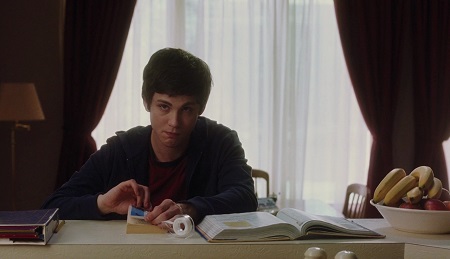

The story follows a young Pittsburgh High School freshman named Charlie (Logan Lerman) who is dealing with all sorts of personal trauma and isn’t certain he’s going to be able to emotionally function during this new stage of his life. Two seniors, brother-sister duo step-siblings Patrick (Ezra Miller) and Sam (Emma Watson), take him under their wing, opening his eyes to a larger world and introducing him to experiences that will redefine his ideas of what high school can be as well as put him on the path towards healing deep-rooted psychological scars.

In past interviews, Chbosky had mentioned how the general path his novel, and now subsequently his film, takes was personal but not necessarily autobiographical. Like a lot of authors, this was a point he was very interested in speaking more on but also one he just as fervently didn’t want to over-explain. “How do I put this?” he asks gingerly. “Some of the stuff that happens to Charlie happened to me. Some of the stuff happened to other people. Like all stories, it’s a mixture, and I’m not sure trying to elaborate on the final mixture of what’s personal to me and what happened to others and what I just made up is a good thing.

“I can say this because I want to give you a real answer, but I do need to keep off of the table what is what. The important thing is that Charlie’s worldview is mine. Charlie’s genuine desire for people to be happy is mine. I have at times put people before me and thought that counted as love. ‘We accept the love we think we deserve,’ is a line I wrote because it was my own response to why I let people treat me badly and why the people that I loved, who deserved so much more, let themselves be treated so badly. I wanted to create a line we could all have ownership of. To me, Perks is a combination of my nostalgia of being young but also my hope for every young person past, present and future.”

One of the more remarkable aspects of both the film and the book are how profound they are in regards to the high school experience. Even though things are set during the early 1990s, there is a universality to Charlie’s story that’s immediately relatable to viewers and readers of virtually every age and every demographic, the story speaking to the core of the individual teenage experience.

“This story, it could be set anywhere,” says Chbosky with a smile. “But that was the point. There’s this thing in Ken Burns’ Jazz. Remember those shots of all the young girls screaming their heads out about Artie Shaw? Artie Shaw. Justine Beiber. There is no difference. The thing that is eternal is not the performer, it is the shouting teenage girls.

“There are certain things that will always be in adolescence. That sense of longing. Feeling alone. Feeling nobody else gets this. Yet everyone does get it, and even if you know that everyone does get it you still think you’re the only one that gets it.

“I make a joke sometimes that whenever someone stops you and says they had the weirdest dream last night, that dream is always boring, I don’t care what it is. But the flipside to everyone’s dreams being boring is that whenever anyone tells you about their first kiss, it is always interesting. Always. Whenever they tell you about the first crush they head, whether it is a boy or a girl, it’s always a great story. Every time.

“Just like a good superhero movie, that’s the origin story. Origin stories are always great, and that’s what Perks is, on origin story about adolescent life, so I’m not surprised so many have related to it as they have. Although, I am grateful that they have. After all, I was just telling them my personal origin story. That it appears to have meant so much to people, that’s unbelievably gratifying.”

It’s hard not to wonder how the almost instantaneous acclaim for the book affected the author. The same goes for the heated criticism. Certain school districts around the country banned Perks from their shelves, while in both 2006 and 2008 the American Library Association named it one of the top ten most frequently challenged books.

“I was very surprised,” Chbosky admits candidly. “The very happy accident in all of this was that I wrote for personal reasons but you still publish in hopes people who read it will relate to what you have to say and not feel alone. Every time I get a letter, every time I meet somebody and they tell me this was their own high school experience, the person who doesn’t feel alone is me, over and over and over again. It’s the best feeling in the world and is the greatest joy. This is the best thing I’ve ever done, telling this story, book and movie, and I couldn’t be happier about that.

“In terms of the vitriol, of the people who object to it, I find all of that strange. It’s strange because they object to it, and this happens quite often, for completely the wrong reasons. They describe the date rape that happens in the book, but not in the movie, I didn’t think it was necessary, as something it is not. It’s a rape. It’s traumatic. It’s horrible. It shows how scarring witnessing that sort of moment can be for Charlie, and it’s completely in line with all the other stuff that happens. It’s all there for a reason, yet some people think I’m trying to be sexy.

“There are moments when you want to say to someone, please, good God, go look in the mirror. This is not sexy. This is not titillating. If it is to you then I suggest you stop blaming me for that and go look in that mirror.”

Chbosky’s answer is illuminating, but it also gets to the nuts and bolts aspect of filmmaking and of adapting popular books for the screen most authors want to avoid. Choosing what to streamline, what to condense and what to jettison completely isn’t easy to do, and leaving those decisions to someone else and washing one’s hands of the project entirely can be freeing.

“It was very difficult,” he admits. “It was about a decade between book and screenplay, and I needed that time to make the tough decisions. But I also missed a step. When you write a book like this and you’re 26 you’re still close to your own High School experiences. When you’re in your late 30’s, I ended up having to do a lot of work emotionally to put myself back in that mindset, to respect what it was that kids go through on an eye-to-eye level.

“Also, I had to find a way to turn a very subjective narrative, the letter format of the novel, into movie language. It’s the cliché that a picture is worth a 1000 words. I had to find those pictures, because it was the only way that I was going to get the density and the catharsis I wanted from the book up on the screen. I wouldn’t have wanted it any other way.

I want people to cheer. It may be selfish to say this, but I want people to love it, the movie, just as I do the story I’d originally written, and I wasn’t going to rest until I came up with a script I felt accomplished that.”

That story lends itself to both cliché and treacly melodrama, two facets of moviemaking Chbosky knew he had to find a way to avoid, if not completely, then just enough so that the audience never noticed their emotions were being blatantly fiddled with. But how to calibrate that? How to trigger the required responses for Charlie’s story to resonate without the film descending to Nicolas Sparks-level platitudes to get its various points across?

“That was the trick, right?” he questions honestly. “I didn’t want to make a sentimental movie. I wanted to make an honest movie. I remember John Malkovich, after he came on to produce the film, was on the set during those first couple weeks, and during dinner he said, ‘I love your script because it has heart. Because it has real heart you don’t need sentiment. Direct this movie like a guy from Pittsburgh and always get the tough take.’ That became a bit of a mantra for me: Always get the tough take.

“Sometimes when you have a really emotional actor, a method actor, that person more than anyone needs a very strong director, because they are not self-editing. They’re just going to go there, to that dark place, and they need someone to tell them to pull back a little or to bring it down.

“In post, that was producers Russell Smith and Lianne Halfon’s job with me. A few other people as well. I told everyone over and over again that I had the book and that I didn’t need the book again, that I needed the movie. If I went off the rails, I needed them to tell me. Luckily, between their feedback and my ‘get the tough take’ desires, we all managed collectively to get it done.”

No conversation about Perks of Being a Wallflower would be complete without asking about the three young actors who make up the central triumvirate. “They’re extraordinary, aren’t they?” responds Chbosky with a gigantic grin. “The whole cast is great, but those three, especially Logan Lerman as Charlie, they are just wonderful.

“There is a little bit of fate that goes into it, casting, and there were times over the years when I was doing rewrites on the script and I would stop and think to myself, what I was waiting for? Why wasn’t I making this movie? Now, that it’s over, I know what it was I waiting for. I was waiting for those three kids, Logan Lerman, Emma Watson and Ezra Miller. If I make it three years ago, they’re too young. If I make it three years from now, they’re too old. Those three were the key.

“And it is also those three at this particular stage of their lives and at this stage of their careers. Emma had so much to prove to herself. That she could play an American and a teenager, someone right around her own age and in a real-world setting. I’ve never seen anyone who needed such permission to just be free, and that’s all she wanted, and it was an honor to help her do it.

“Logan, he brought in the performance that you saw. We auditioned two people and he was number two. There were no other auditions. He was fantastic, and he only got deeper, only got better, as we spent time on the production. He read the book and the script and dug deeper and deeper into it. He was determined. This cool thing happened. There was this screening at Donna Karan’s house and afterward, Paul McCartney came up to Logan and said, ‘You’re brilliant, man.’ How amazing is that?

“Ezra is awesome. I knew him from City Island, and while he was a little younger, I knew that with Logan and Emma basically being raised on film sets that I needed a bit of a wildcard to let them know it was okay to be kids. This was important. Ezra, my goodness, I hit the jackpot with this guy. He’s amazing, isn’t he? Without him, I just don’t think this particular trio of actors would have been as stunning collectively as they were.”

Ultimately, the movie is the movie and the book is the book, and while Chbosky is proud of both, now that the former is going into general release while the latter is finding a newfound surge in popularity, it’s difficult not to wonder what his thoughts on this journey as a whole might be now that it is nearing its end. “I had this moment,” he explains, “and I don’t know how many directors have felt this way as this is only my second movie. I had finished the final mix, and I was a lunatic by that point. So tired. So emotionally drained. I came back to the film after a few months away and I was like, my god, I made that movie? I wanted to shed a tear. It was as pure a moment as you could get.

“I’ll sit in the theatre and I’ll look around, and when people laugh or cry or whatever, I’ll think to myself that we all just get this thing, this emotional thing, that is going on. While I made the movie and while you watched the movie, when it’s all finished it is the thing that is the thing and it remains the thing, it doesn’t get any simpler than that. Our parts in it, the making of it, that’s kind of irrelevant now. I love that sense of community, that experiential moment we can all have collectively. Adolescence, first kisses, how we meet the love of our lives, it’s always interesting. Always. Remember that.”

– Interview reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle