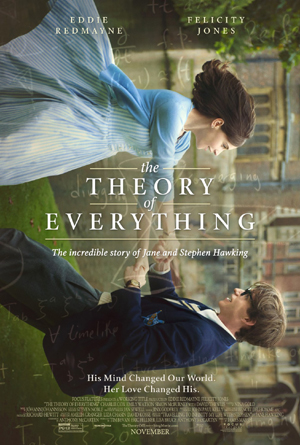

The Theory of Everything (2014)

by Sara Michelle Fetters - November 14th, 2014 - Movie Reviews

Powerful Theory an Enthralling Brief History

Long before he wowed everyone with the 1988 publishing of his best-selling scientific treatise A Brief History of Time, Stephen Hawking (Eddie Redmayne) was nothing more than an exceptionally bright cosmology student at U.K. university Cambridge. It is 1963 and his professor Dennis Sciama (David Thewlis) is a little worried his most apt pupil won’t focus and deliver a doctorate equal to his abilities. The young man would like to find a “simple, eloquent explanation” for what he deems “everything,” the seasoned educator realizing how grand a challenge this will prove to be, urging his student to go right ahead and attempt to compose his theory.

Hawking is 21-years-old, self-effacing in his absolute confidence in his intellectual and scientific abilities, his arrogance countered by a mild-mannered tenor those closest to him are intoxicated by. He has also just met the beautiful, charming and equally self-assured Jane Wilde (Felicity Jones), and even though she’s a devout Catholic from a good Christian family she doesn’t hold his atheism against him so why should he in turn hold her religiosity against her? Their mutual love is instantaneous, and it’s only a matter of time before they’re walking down the aisle as husband and wife.

However, before that can happen the budding scientific genius is given the diagnosis from doctors that will affect the course of his life from that point forward. Told he has motor neuron disease (a.k.a. Lou Gehrig’s Disease, also known as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or ALS) and given only two years to live, Hawking would, of course, go on to, not only wed Jane and father three children, but also bring forth one of the great scientific dissertations of the 20th century. Love him, hate him or just don’t understand a darn thing it is he’s talking about, it’s still safe to say that his stamp on the world as we now know it borders on unquantifiable.

Based on the memoir Travelling to Infinity: My Life with Stephen written by ex-wife Jane Hawking, with a screenplay by Anthony McCarten (Death of a Superhero), director James Marsh’s (Man on Wire, Shadowdancer) mesmerizing The Theory of Everything is a potent drama that rises well above the more maudlin aspects of the story’s inherent disease-of-the-week melodramatics to become electrifying and vital. Superbly acted by Redmayne and Jones, filled with astonishing moments of beguiling intimacy and breathless power, the movie is a subtle examination of a relationship unfolding under the most incredible of circumstances.

The movie is at its best when it focuses directly on how Stephen and Jane navigate their ever-evolving relationship as ALS slowly begins to ravage the scientist’s physical, but not his mental, faculties. The effect this has on the couple, how they rise to the challenge or fail to meet the tests put in front of them, all of this is examined in much the same sort of clinical, yet still relatable, detail that Hawking’s work is known for. Marsh allows the actors to do most of the heavy lifting, stripping out much of the dialogue and additional fits of exposition, allowing Redmayne and Jones to explore the complexities of given situations through body movements, eye contact and facial expressions alone.

Both rise to the occasion. Redmayne makes Hawking’s ALS journey palpable, puts the viewer right there with him as he slowly but surely loses his physical faculties even while his mental ones continue to sharpen. He doesn’t make an attempt to soften any of the hardships, doesn’t want to make the audience shed tears just for the sake of doing so, instead focusing on delivering a more three-dimensional portrait of the scientist refusing to sentimentalize either him or his choices as things progress. There is a fierce, undeniable tenacity that goes well beyond the obvious physical transformation, Redmayne disappearing inside his portrait of Hawking to the point one almost forgets he’s an actor playing a role and not the man himself.

With that being so, as obviously Oscar-worthy as Redmayne might be (and, considering the nature of the role, and knowing the history of Academy voting, his nomination is inevitable), if you can believe it, Jones is the one who ends up standing out as far as I am concerned. Her task is gigantic, spending most of the film reacting to what her costar is going through, very seldom dictating what is happening up on the screen for herself at any given moment.

She’s incredible. Already haven given one of the year’s better performances in the criminally under seen Breathe In, having already turned in Oscar-worthy work in film’s as intimate and involving as 2011’s Like Crazy and last year’s The Invisible Woman, what Jones does borders on breathtaking. Jane’s fierce determination to see her husband’s work done is coupled with her growing despair at having so much responsibility thrust upon her, the actress making all of the woman’s conflicting emotions feel real, genuine, all of them coming straight from the heart. Jones traverses an intellectual and emotional minefield with beauteous simplicity, saying more with a glance and a gentle nod than most can with an entire page of dialogue. She’s outstanding, and as of right now this is without question one of the finest performances I’ve had the pleasure to witness in all of 2014.

McCarten’s script, as good as it is, does feel a little too ephemeral, too nondescript at times, moving through the years a little haphazardly, glossing over large portions of the Hawking story in order to get to the triumphant publishing of his signature work. The reasons behind Stephen and Jane’s ultimate uncoupling are there, easy to see, but not nearly as well explored as they potentially might have been. Marsh does what he can to flesh out these sequences of marital unease, but they just don’t mesh inside the greater framework as comfortably as I’d have liked them to and I can’t say this part of the pair’s story resonated as strongly as the rest of it did.

Be that as it may, The Theory of Everything is a wondrous, startlingly effective drama. Marsh once again shows a talent for narrative dramatics that’s exceptional, using his skills as a master documentarian to give things a bristling, conspicuously enthralling legitimacy that’s undeniable. Stephen and Jane see their story told with a vital enthusiasm that’s both breathtaking and timeless, their brief history together without question a tale of teamwork, heartache, compromise, commitment, love and achievement that’s as particular to them as it is universal to us all.

Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 3½ (out of 4)