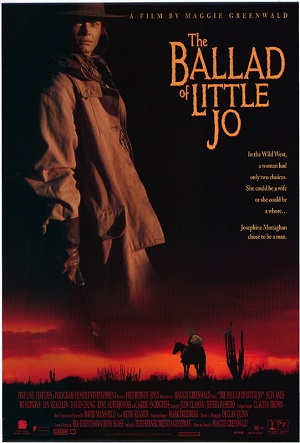

Unforgettables: Cinematic Milestones #20 – The Ballad of Little Jo (1993)

by Sara Michelle Fetters - September 27th, 2023 - Features

Maggie Greenwald’s revisionist 1993 Western remains a bleak feminist drama of gender identity and self-determination

NOTE: This feature originally appeared in the August 25, 2023 edition of the Seattle Gay News. It is reprinted here by permission of the publisher Angela Craigin.

The first time I watched Maggie Greenwald’s revisionist Western, The Ballad of Little Jo, I almost walked out of the theater. Not because the film was bad — far from it — but more because many of its images and themes were hitting too close to home. Its depiction of gender nonconformity in the fabled “Old West” of the late 19th century struck a nerve, and as a freshman at the University of Washington struggling to deal with their own issues regarding gender identity, watching this bleak, uncompromisingly dark drama proved difficult.

I’ve revisited Greenwald’s best-known feature on occasion over the past 30 years, and I’m continually struck by how brutally chilly it is. While certain elements haven’t aged particularly well, and while its relationship to the true story of small-town Idaho rancher “Little Joe” Monahan is flimsy at best (and insulting at worst), there is still a certain visceral power to this tale that the filmmaker has so meticulously constructed.

Much like Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven or Robert Altman’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller, this is a confident evisceration of Hollywood archetypes and tropes about the West. This feminist takedown of backwoods, male-dominated communities is purposefully unsubtle and frequently stunning in its steadfast cruelty as it clubs the viewer into submission. But there is also a quiet, forlorn beauty to Greenwald’s epic that’s mesmerizing, and the affection the director has for her hero is readily apparent first frame to the last.

Suzy Amis stars as Jo Monahan, and even though she never disappears entirely into the role (or is particularly believable at maintaining a masculine façade), this somehow remains one of the most spellbinding performances of the talented character actor’s career. Amis combines a raw physicality with an emotional dexterity that’s extraordinary. It’s a unnerving portrait of a person desperately trying to be their true self, only to be continually bludgeoned by a society that wants to fit them into a box that matches its conservative patriarchal point of view.

The story begins with Jo — known by her hypocritically puritanical family as Josephine —being cast aside after giving birth out of wedlock. After initially heading west in all her frilly Bostonian finery (including a fancy bonnet and a whimsical parasol), it doesn’t take the young woman too long to figure out that she’ll need a more masculine disguise if she ever hopes to survive. Finally settling down in the windswept, isolated emptiness of Ruby City, Idaho, Jo buys a small sheep ranch and begins to build a life, and the townsfolk begrudgingly accept the smallish, somewhat feminine newcomer as one of their own.

It’s impossible not to notice how Greenwald posits that Jo’s Transgender identity is a matter of survival. The historical record is hazy on that front, but it seems pretty clear that the real “Little Joe” embraced their male self and made the best life that was possible during the 1880s and ’90s. As such, this film doesn’t dive into key issues involving Trans self-expression, sexuality, or gender ideology of the period nearly as much as it could have.

There are also issues involving Tinman Wong, a Chinese immigrant whom Jo saves from being lynched, only to have him forced upon her as a live-in ranch hand. If not for David Chung’s superlative performance, Greenwald could be accused of reinforcing effeminate cultural stereotypes. Even though Wong turns out to be far more complicated, self-assured, and intelligent than he appears, the way his character is presented is more akin to Hollywood B-films of the 1930s and ’40s and thus does not entirely fit into the rule-breaking ethos Greenwald otherwise is aiming for.

But The Ballad of Little Jo continues to haunt me all the same. Greenwald may have toned down the more overt LGBTQ elements, but they nonetheless remain front and center. For a 19-year-old, far from home, living on their own for the first time, and with no one who understood what they were going through close by, seeing Jo meticulously construct an alternate gender identity in the face of such overwhelming odds, while also under an overly invasive microscope, was disquietingly powerful. There is a majesty to these images of Jo slowly but surely becoming their true self that I instantly responded to, and the fact there was no one I could talk to about what it all meant to me at that moment was borderline heartbreaking.

I don’t know what the legacy of this film is, now three decades after its original release. Magnificently shot by Declan Quinn (Sylvie’s Love) and featuring exquisite, consistently discomforting supporting turns from heavy hitters like Rene Auberjonois, Ian McKellen, Anthony Heald, Carrie Snodgrass, and a never-better Bo Hopkins, there’s certainly plenty here that’s more than stood the test of time.

For me, however, The Ballad of Little Jo remains essential. Even with its missteps, my connection to Greenwald’s film remains strong. Its ethereal, penetrating tenacity as it strips Western mythology to shreds and reveals its blatantly misogynistic center is striking, and the tragically haunting truthfulness of its final images is impossible to forget.

Now celebrating its 30th anniversary, The Ballad of Little Jo is available to purchase on DVD.