“Everybody’s Talking About Jamie” – Interview with Jonathan Butterell

by Sara Michelle Fetters - September 10th, 2021 - Interviews

Finding Joy

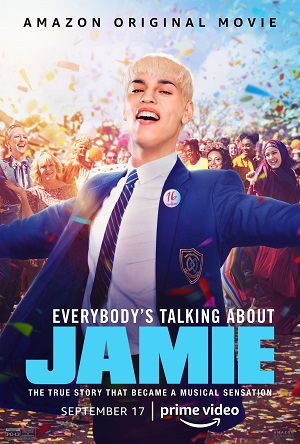

Everybody’s Talking About Jamie director Jonathan Butterell on bringing the West End musical sensation to the big screen

Inspired by the true story outlined in the 2011 documentary Jamie: Drag Queen at 16, the musical sensation Everybody’s Talking About Jamie has made the leap from London’s West End stage to the big screen with energetically wholesome aplomb. Overflowing in empathetic kindness, this shockingly great motion picture took me by complete surprise. I enjoyed almost every second of it, and from its toe-tapping first number to its tearfully sublime show-stopping climax, director Jonathan Butterell’s adaptation euphorically hits all the right notes.

The story follows 16-year-old Jamie New (newcomer Max Harwood). After being given a present of an expensive pair of red high heels for his birthday by his loving, if often perplexed, mother Margaret (Sarah Lancashire), the flamboyantly gay youngster reveals to his best friend and confidant Pritti Pasha (Lauren Patel) that he wants to be a drag queen. What’s more, he also wants to attend the prom in a dress.

With the dual support of Margaret and Pritti, Jamie seeks guidance from aging drag legend Hugo Battersby, aka Loco Chanelle (Richard E. Grant). He also hopes to earn the affection of his father, Wayne (Ralph Ineson), whom he seldom sees, as his parents divorced when he was a youngster. Through it all, Jamie learns what it means to take charge of your life and stand up for what you believe in without destroying or selfishly belittling others in the process.

I sat down with Butterell over Zoom to chat about his new film. The following are some edited transcripts from our lengthy conversation:

Sara Michelle Fetters: What is it about this story and its kind of crazy wholesomeness that attracted you and made you want to go from the musical production into crafting a feature-length film?

Jonathan Butterell: This story started with me seeing the documentary Jamie: Drag Queen at 16. I saw this young kid get off a bus, a 16-year-old boy, get off a bus in a working-class community, a community I knew and which was very similar to the community I grew up in myself, and say directly to camera, “My name’s Jamie. I want to be a drag queen.” Then the camera pans down to him wearing this fabulous pair of heels.

I was hooked. I watched his mom support and love him and hold him. I watched the community around [Jamie] make a safe space in which he could be himself. I knew I needed to tell this story. I could feel it.

You said “wholesomeness” and I like that word. I can go even further than that. This story is about finding the center of this particular someone’s joy. I find putting your joy out to be an act of defiance in some ways. It’s going, “This is who I am. This is where I find my joy. I need a place in which to express it.”

But joy shouldn’t be an act of defiance. It should be a very natural act that we all have, and I found Jamie to have such courage in doing this. It was inspirational, and I wanted this story to be out in the world. Particularly now. With all that we’ve been through with regards to all being locked away from any sense of community, but also because we’ve lived in an entrenched world for such a long time, I just wanted the world to celebrate each and everybody’s individual joy.

SMF: This might be what makes the film so remarkable. It’s just so kind. We don’t see a lot of that right now, especially with everything that we’ve been through. It almost feels revolutionary watching this story in the context of a musical. What do you think?

JB: Yes. That was the intent from day one between Dan Gillespie Sells, Tom McCray and myself. I grew up a long time ago in an Irish Catholic working-class community. Contrary to all belief, I experienced kindness around me. I know that’s unusual. I know not everybody experiences that. But I knew the power of this, and I knew it was revolutionary.

It’s such an easy word: kindness. It’s such a simple thing. It’s a very simple act to find that kindness in your heart. I like “kindness” better than the word “love” in many ways, because “love” is such a complicated word. It means so many things to so many people. But a simple act of kindness? We understand it in a very clean way.

I’m enjoying your response to it being kind of revolutionary, because that was the intent. We never wanted to flag-wave, because if we’re flag-waving that entrenches us in some ways. I never want Jamie to be a victim.

I wanted this not to be a coming-out story for the simple fact that there’s been a million coming-out stories, some of which have been beautifully done, but this wasn’t that because Jamie’s authentic and fully himself right from the beginning.

For any 16-year-old, the major struggle is, “Who am I?” and “Where’s my place in the world?” That’s normal. I wanted that for Jamie. He can’t represent his whole community, because our community is so diverse. He can only be one voice of a million diverse voices within that community. But in this one voice, I also wanted him to say, “I can represent everyone.”

Look, straight white men get to do this in stories often. They get to represent the “everyperson” or the “everyman.” I wanted Jamie, effeminate queer hero, to be able to go, “I can speak for us all. I can speak for the young and the old and the black and the white and the queer and whatever gender you identify as. I can represent everybody in that respect.” Because we all know what it is to step out into the world and try to find our joy. That’s part of being human.

SMF: I think the two primary relationships in the film are one of the keys to what you’re talking about. That’s the relationship between Jamie and his mother Margaret, and then the one between Jamie and Pritti. Those relationships are far more complex than I think they initially appear. There’s a lot going on. You guys pack a multitude of emotional nuances into those journeys.

Was there any trepidation that you were almost making these relationships too multifaceted? I hate to ask, because I don’t think that’s necessarily possible, but when you’re dealing with audiences, it is unfortunately something that has to be considered.

JB: I’m going to be diplomatic. Sometimes you have to fight to maintain what I would just call complex reality. We’re all a mess. We’re just a mess. Being a mother is a mess of a thing. Being a dad is a mess of a thing. It’s all complicated.

I can’t imagine what it must be like for a mother who doesn’t fully get it. Margaret’s trying to learn along the way. She gives him the shoes, not knowing what they mean. She gives him a pair of shoes to walk in that may end up making a very rocky path for him, but she still gives them to him because, even though he may stumble in these shoes, he’s going to have to stumble in order to learn.

She’s also saying, “I’ve got to let him be even if everything in my body’s wanting to protect him and stop him from falling.” Those are two contradictory emotions. But Jamie needs to be free. Even if being free means he’s going to get hurt. That’s rough for a parent.

I think the same with Pritti. Pritti does not understand Jamie. Never mind her cultural background — her personality is just different. But again, she tries. All she puts forward is her love of Jamie. She’s there for him. She says to herself, “I’m his friend, even if that means pulling him up to say you’re going too far in this one moment in time.” She’s a true friend in that way.

SMF: When you’re translating a true story into a cohesive, audience-friendly story for a West End musical, how do you balance all of those varying aspects of Jamie’s tale?

JB: I suppose the answer to the question is the music. What a musical does is it brings another version of storytelling into the equation. I wanted to make sure that the music was pop. I wanted it to be stuff people listen to on their radios. Pop can be highly, highly sophisticated, and it felt right for this production. I didn’t want it to feel oversophisticated of for audiences to feel like they just didn’t get it.

Then, because it’s Jamie and he’s 16, that pop world allowed his imagination to fly. It allowed my imagination to fly. Particularly with this film, I could go all over the place. I could take Jamie into the pop video land. I could take him into this most fabulous club with 500 amazing creatures or down this great fashion catwalk. I could transform his canteen at school into an amazing ballroom because his imagination flies to that place.

Balancing fact and fiction, we created Jamie New as opposed to Jamie Campbell specifically for that reason. We wanted to allow Jamie Campbell the freedom to distance himself from our story if he wanted to. He could say, “That’s not me. That’s Jamie New.” He didn’t feel the need to do this, but we felt it was important to give him that option.

I remember when they saw it for the first time, the theater piece, Margaret tapped me on the shoulder and said, “How did you know? How did you know, we’ve had those conversations in those kitchens? You weren’t there.”

We just used our imaginations. We all have moms. We’ve all been in that place, Dan, Tom and I. We have similar backgrounds. We used our own stories and our own imaginations. There’s something universal in Jamie and Margaret’s story. It’s universal.

SMF: Talk to me about Max Harwood. When did you know he was Jamie? What was that like seeing him come alive as you were shooting the film?

JB: Finding Jamie was a big task. You’re trying to find a young person who can play 16 and unashamedly tap into their effeminacy. It was important to me to have an effeminate hero because I feel like you never see that. They’re always the sidekick. The fun person. Or, worse, the person who gets beat up and is left in the corner. Having someone who was comfortable and at ease with regards to their feminine side who could sing, dance and had the full range of acting emotions, that’s tough to find.

We put out an ask on social media for anybody across the whole of Britain to audition. Max sent in a little one-minute video of himself in his bedroom in which he spoke candidly about his life and his love of Drag Race. He loved playing around with make-up. He felt he really understood this story. He used to dress up as his sister when he was little and get her to play Kenickie to his Rizzo.

I just thought he was charming. I thought Max had a glint and a charm and a slight magic from that video, so we asked him in. He was one of about five young men who auditioned. They were all good, but Max had all the skills. Although he’d never done any professional acting at all before. Nothing. We got him straight out of school. But he still had all the skills.

When you ask what makes somebody special? It’s ephemeral. You can’t put your name on it. To watch Max grow throughout the whole process, to have a young man who’d never been on set before suddenly be acting with Richard E. Grant on his first day, with an Oscar nominee, that very first day, that was beautiful to watch.

Actually, what was happening off-screen was happening on-screen. This elder mentor was looking after somebody who is aspiring to be what they were. Or in this case, what they still are. Richard looked after Max so beautifully, in the most unpatronizing and beautiful way. It was wonderful to watch.

I think that was captured that in the film. It’s there. The essence of it is there.

SMF: I have to ask, what would you do if Richard suddenly found himself a two-time Oscar nominee because of this film?

JB: Oh my! [laughs] Wouldn’t that be something? I can’t think like that. I can’t! I’m just a boy from Sheffield. It’s weird that we’re here in the first place.

I loved telling this story. I think all the actors brought so much of themselves that they deserve whatever accolades may come their way. I wish it for all of them. But in the case of Richard, to be in this conversation, it just feels very weird to me. People keep bringing it up and it feels very weird.

I’d love him to take that up on that stage and pick up that trophy. But I know for Richard, that’s not what it’s about. From the onset, he wanted to be involved in telling this story. He’d never put on drag before or done anything like this. He felt it was a stretch.

I didn’t think it was too much of a stretch at all. I thought Richard had it in him all the time, and I think he’s wonderful in the film. So I would love it. But I can’t think about that.

SMF: There is that moment in the shop where Jamie sees the video. That might be one of the more extraordinarily subtle bits of storytelling I’ve seen all year. We get Hugo/Loco Chanelle’s entire story in the context of a two, three-minute VHS video. It’s devastating.

JB: It was vitally important to Dan, Tom and me to get that moment into the film. Vitally important. We were on those marches. In fact, one of the scenes was the Section 28 march (Section 28 was a law passed by Margaret Thatcher that banned the promotion of homosexuality). We went on those marches.

I felt it vital that we tell this story. It’s a story of generations. I wanted to make sure we passed that down. But how to do it? For me, it’s kind of told by Hugo’s lover, who’s not chronicling necessarily the politics of the time, but instead what he and his partner are doing together as a couple. I think that makes it personal as opposed to polemic.

But it is political. We were political at that time. We were radical at the time. We were out there trying to change the world.

SMF: With all of that in mind and with everything that we’ve talked about, what do you want audiences to take away from the film? What do you hope that they’re talking about? Not just talking about Jamie, but talking about themselves and their lives and everything going on in the world. What is the conversation?

JB: If I was to describe it as a feeling, I’d like them to take away that joy we talked about earlier. I’d like them to look at what that joy has done to them and for them. Joy opens your heart, and when your heart gets expanded, even a little bit, it allows that little bit of fear to get pushed out. To know that we’re all capable of experiencing that joy. Who are we? Where do we find our joy? These are big questions we too seldom think about.

But I never went into crafting the musical or making this movie with the intention of exploring any of that. It’s a consequence of the story. It’s a consequence of Jamie Campbell’s courage. That’s what inspired me, and I hope it’s what inspires others. I just wanted to tell that story. I didn’t go into any of this to preach. So if audiences relate or respond to any of Jamie’s story the same way I did, if they take some of that joy away with them, that would be amazing.

– Interview reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle