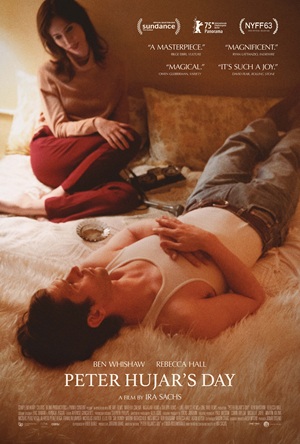

Peter Hujar’s Day (2025)

by Sara Michelle Fetters - November 14th, 2025 - Four-Star Corner Movie Reviews

Austere Peter Hujar’s Day is a Priceless Snapshot of Art, Life, Love, and Undying Friendship

Ira Sachs has always had an in-depth understanding of the power of language. He’s been equally astute in his grasp of the riveting authority of silence. At their best, his films showcase an inner poetic lyricism that speaks volumes and are captivatingly universal in their powerful eloquence. There’s something incredible about that, especially given that his films have such brazenly Queer content and proudly Gay characters, almost all of whom are doing their best to navigate through various relationship anxieties.

Love Is Strange, Keep the Lights On, Passages — these are three of the features Sachs has written and directed that strike such a chord. The emotional push and pull within their dissimilar dramatic travelogues is haunting in its touching specificity. Sachs achieves a level of character-driven authenticity that transcends eras, genders, and cultural variances. It’s magnificent.

Sachs’s latest, Peter Hujar’s Day, showcases the filmmaker at his best. At first glance, his adaptation of writer Linda Rosenkrantz’s transcripts of her daylong 1974 interview with New York photographer Peter Hujar seems as if it would be more at home on an off-Broadway stage than inside a neighborhood cinema. But Sachs takes this conversation between close friends and makes something heartbreakingly profound out of it. This drama attacks the soul with calmingly intoxicating relish. The somber beauty of two friends engaging face-to-face as one recounts a day in their life to the other is stratospheric in its not-so-mundane resonance.

The idea was simple enough: Rosenkrantz (Rebecca Hall) wants to write a book in which she tasks an assortment of notable people to document an entire day, which they will then recollect to her in a detailed conversation. One of those she invites, Peter Hujar (Ben Whishaw), is an esteemed photographer best known for his black-and-white portraits of celebrities, social gatherings, the Gay liberation movement, and other high-profile events.

While the book never materialized, Rosenkrantz kept the transcript for her interview with Hujar, finally publishing it as a 36-page novella in 2021. Working in tandem with the two actors and director of photography Alex Ashe, Sachs’s adaptation follows the source material virtually word-for-word. What he and his crack team do from there, however, is produce magic on a seismic level. His film is a time machine that takes the viewer back to 1970s New York with phantasmagoric precision. Rosenkrantz and Hujar leap off the screen, and there were moments when I felt like I was sitting on the edge of the bed, at the kitchen table, or leaning against a ledge, looking over the concrete jungle of the Big Apple right alongside them.

Taking visual cues from the photographer’s now-timeless images, the film is an ephemeral dreamscape of reality and imagination. Ashe’s camerawork, while almost entirely contained within the austere interiors of Rosenkrantz’s apartment, is reminiscent of Gordon Willis’s seminal work on other New York stories like Manhattan, Klute, and Annie Hall. While the camera isn’t entirely stationary, movements are kept to a bare minimum. One second, Ashe zooms out to capture Hujar’s expressive gestures and hand movements. The next, he craftily moves back in for a close-up centered on Rosenkrantz’s expressively alluring eyes as she actively listens with empathetic fascination to each and every word her friend has to say.

As with production designer Stephen Phelps’s exquisitely detailed period work and the suitably weathered and lived-in clothes crafted by costume designers Eric Daman and Khadija Zeggaï, nothing is out of place, and every detail augments the overall authenticity of the production. But Sachs smartly doesn’t let these elements overshadow the verbal gymnastics Rosenkrantz and Hujar are engaged in. While his film has a surprising surplus in style, what it offers up in emotionally multifaceted substance is even more extraordinary.

Both Hall and Whishaw are sensational, even if what is asked of them couldn’t be more different. The former says maybe a tenth of what her co-star does. Granted, this shouldn’t be shocking, considering that this is by design, as Rosenkrantz wanted Hujar to do the majority of the talking. Yet, that does not make Hall’s performance any less masterful. Rarely has a nonverbal central role taken on such shattering articulateness. The actor’s body movements, her eyes — those penetrating, all-seeing eyes — stopped my breath. Hall is sublime.

Whishaw’s work is every bit as outstanding. His rat-a-tat-tat, rhythmic meticulousness as he recounts Hujar’s day is intoxicating. His arms are in constant motion, his hands effetely passing a seemingly continually lit cigarette back and forth as if it were on a string attached to one of his wrists like it was a child’s helium-filled balloon. Whishaw brings a musicality to Hujar’s recollections that play in symbiotic coordination with the film’s George Gershwin–heavy soundtrack. He’s a constant wonder.

Keeping up with all of Hujar’s name-dropping as he recounts everyone he recently worked with, encountered, or thought about during his day — a mind-blowing roster of giants, ranging from Lauren Hutton to Susan Sontag, Allen Ginsberg to William S. Burroughs, Rod Stewart to Stevie Wonder, all leading to a final tally of 40 or so names — can be a lot of work. It’s doubtful anyone will know who all of them are, let alone the majority (I had to look several up), and I do imagine a fair share of viewers may find that frustrating.

I did not. Hujar’s casual cadences reminded me of Monty Woolley in 1941’s acid-tongued holiday classic The Man Who Came to Dinner. Not knowing everyone being referenced is both part of the fun and also cements that character as a man who walks in and out of a multitude of worlds with blasé ease. Hujar isn’t an elite, and while he is awed by many of them, he is decidedly unafraid of working and residing within their spheres.

But the heart of Peter Hujar’s Day is that friendship between the photographer and the writer. Rosenkrantz loves this man, and it is readily apparent that Hujar feels the same. Their platonic stillness has a rapturous malleability that moved me to a tsunami of happily cathartic tears. Sachs delivers a picturesque chronicle of everyday life that’s breathtaking in its verisimilitude. It captures a time and place that may be long gone, but that doesn’t keep it from understanding the here and now in all its complexity and minutiae. If a picture can be worth a thousand words, then this film offers up 76 mesmeric minutes of them that are nothing short of priceless.

– Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 4 (out of 4)