Crowley’s Boys in the Band Still Have Plenty to Say

Do we need a 2020 version of Mart Crowley’s groundbreaking play The Boys in the Band? Does it still resonate, polarize, educate and shock a viewing audience the same way it did back in the late 1960s or like it did in William Friedkin’s still controversial 1970 film version? I don’t have those answers. This play, Friedkin’s motion picture, I’ve always been one of those who’ve been kept at arm’s length from the material, so it’s admittedly difficult for me to fully comprehend my feelings as it pertains to this latest adaptation.

Part of that likely has something to do with the fact I was still firmly trapped within the closet when I first watched the film back in the early ’90s while in high school. I knew I was transgender, and it was sheer torture keeping all of that inside. As such, watching Friedkin’s film was an eye-opening chore. I didn’t see myself in any of these characters, yet on a deep level I could still relate to much of what they were going through. By the time it was over my stomach was in such knotty tumult I sort of wished I’d never put the tape in the VCR and pushed play roughly two hours prior.

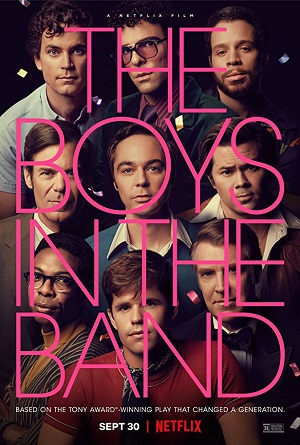

I admit all of this in the spirit of being honest as to how I felt walking into director Joe Mantello’s (Love! Valour! Compassion!) new take on Crowley’s play. After a successful 2018 Broadway revival, the filmmaker reunited the core cast members of that Tony-winning production for this Netflix film version, including Jim Parsons, Zachary Quinto and Matt Bomer. Mantello’s adaptation, written by Crowley (who sadly past from complication from heart surgery back in March) and Ned Martel, is exquisitely composed and perfectly performed, and for those reasons alone his version deserves top marks right across the board.

But I still can’t fully embrace the material. This is a very male look at gay life, and while much of Crowley’s scenario is sadly not near as dated after five-plus decades as I would like it to be, there is still a moderate distancing effect taking place as far as it pertains to broader LGBTQ experiences. While aspects are undeniably universal, this still can feel like something of a one-sided debate that forgets or discounts large swaths of the broader community.

That’s nitpicking, though. This is what pre-Stonewall life was like for many gay Americans, and watching these men deal with all their issues regarding sex, gender, race and identity during one tumultuous night is a continuous punch to the gut that’s heartbreaking in its emotional exactitude. No one gets out of this New York apartment unscathed, each man forced to look in the mirror, maybe not in a new way, but at the very least a slightly different one, and while for some that can be seen as progress, for others it ends up being a tragedy from which they might never recover.

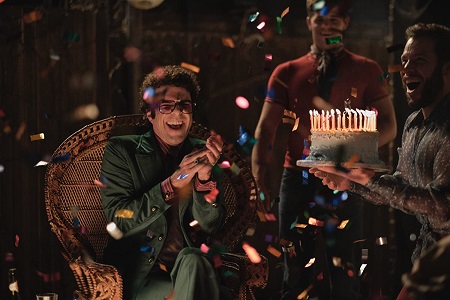

The plot hasn’t changed. A group of close-knit friends meet at Michael’s (Parsons) West Village condo to celebrate the gloriously bitchy Harold’s (Quinto) birthday. Unexpectedly crashing the evening is one of Michael’s old college chums Alan (Brian Hutchison). He’s hoping to find a sympathetic ear to vent some mysterious secret to, believing his Georgetown roommate will be able to help him out for reason best left undisclosed. But his appearance has a catastrophic effect on the evening, and suddenly all of the party’s attendees are forced to come to grips with what it means to be a gay man in the 1960s in ways they’d rather not speak aloud if it were at all possible.

Several standout bits cannot be ignored, not the least of which is Bill Pope’s (The Matrix) marvelous cinematography. His camera navigates the numerous corners, side rooms and staircases of Michael’s home with cunning virtuosity. Pope’s visual ingenuity is never smothering and it refuses to call attention to itself. Yet there is still a kinetic grace to what he is doing that is frankly stunning, his deft use of production designer Judy Becker’s (American Hustle) immaculately constructed interiors beyond reproach.

Next is Quinto. He delivers a towering, unforgettable performance. It may take a bit of time for the chronically late Harold to arrive, but once he did I wouldn’t have been able to take my eyes off of him had I even wanted to try. Quinto provides an instant jolt of electricity I did not see coming. There is an effortlessness to his line delivery that held me spellbound, and whether blithely delivering a devastating putdown in Michael’s direction or lasciviously salivating over his himbo birthday present boy-toy (Charlie Carver), everything the actor does drips with passionately acidic complexity. This is one of 2020’s best performances.

The rest of the cast is equally up to the challenge, each finding ways to inhabit their respective roles with dexterous confidence. Parsons has the unenviable task of doing the majority of the expository heavy-lifting, Michael’s frequent monologues starting almost all of the primary discussions that end up happening throughout the story. While at first I found him to be slightly annoying, as events progressed what the actor was doing and how he was tackling his character began to win me over, so by the time he and Bomer passed quiet looks of despondent cathartic understanding I couldn’t help but shed a couple of lonely tears in hushed appreciation.

Crowley’s play was ahead of its time. His look at gay life in the 1960s was unheard of then, and it still has plenty to say on the subject now. But as good as The Boys in the Band might be, I still find I appreciate what the author is saying more than I can personally relate to most of his words. None of which minimizes the strength of Mantello’s adaptation, and even with these reservations I still hope audiences give the film a look as soon as it becomes available for them to do so.

Film Rating: 3 (out of 4)