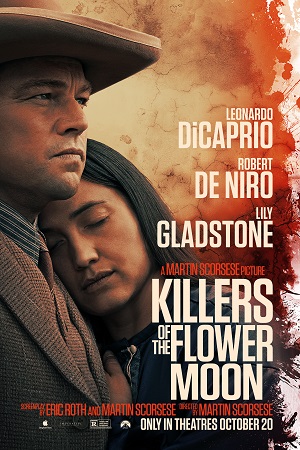

Killers of the Flower Moon (2023)

by Sara Michelle Fetters - October 19th, 2023 - Four-Star Corner Movie Reviews

Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon is an Epic Accusatory Masterpiece

Martin Scorsese needs no introduction. For almost six decades, his feature films have burrowed into the human condition. They are fearless. They are uncompromising. They are essential.

These range from the dark, dingily lit interiors of Mean Streets to the washed-out, steel-gray blues of Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore to the black-and-white pugilistic forcefulness of Raging Bull to the emotionally acidic claustrophobia of The Age of Innocence. The adrenalized Steadicam brilliance of Goodfellas is electrifying, but so is the turbo-charged, bright-green felt of The Color of Money. Scorsese has tackled religion and faith with prescient — some might even say vicious — curiosity in the spellbinding trifecta of The Passion of the Christ, Kundun, and Silence, and he’s even dabbled in psychological horror with his remake of Cape Fear and the fractured psychosis of Shutter Island.

But this is just the tip of a massive cinematic iceberg. Dark, pitch-black comedy? Take a look at After Hours, The King of Comedy, or Bringing Out the Dead. Legendarily immersive concert films? How about The Last Waltz or Shine a Light. The highs, lows, and morally ambiguous in-betweens of the so-called “American experience”? Start with Who’s That Knocking at My Door, travel through New York, New York, take a pit stop with Taxi Driver, and stare into the abyss of unfiltered madness with Gangs of New York or Casino.

Let me be clear: it is impossible to talk about the last 50 years of independent and Hollywood film and not mention Scorsese. (It is equally unfeasible to not mention him when talking about the curation, celebration, and preservation of cinema from every region of the globe, going back a full century.) He’s an unassailable legend, and while some of the pictures he’s directed are undeniably better than others, even Scorsese’s misfires are worthy of multiple looks and in-depth dissection.

So, when I say that Killers of the Flower Moon, an adaptation of David Grann’s nonfiction book of the same name, is up there with the director’s best work, I do not make such a proclamation lightly. Scorsese and co-writer Eric Roth (The Insider) have constructed a work about a horrifying American historical calamity that cut deep and left scars that have lingered for generations. It is a damning condemnation of a country built on racism, misogyny, and genocide, all showcased in a mesmerizingly intense, period Western procedural thriller so fully realized that I could feel the dirt dig its way underneath my nails and smell the sweat dripping off of the disheveled cowboys as they drank moonshine, coupled oil wells, and shot unsuspecting members of the Osage tribe in the back of the head.

Mostly taking place during the 1920s, the story follows WWI veteran Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio) as he arrives on the Oklahoma reservation to work for his uncle “King” William Hale (Robert De Niro) and brother Bryon (Scott Shepherd) by driving a taxi. The Osage are by far the richest tribe residing in the United States, their land littered with one oil well after another. Ernest falls in love with one of his frequent passengers, the confidently reserved Mollie (Lily Gladstone), and before either of them knows it, suddenly they are married.

That’s the warm and fuzzy stuff, but even this romance has a simmering hint of menace devilishly residing underneath, just waiting to boil over. King is not the benevolent “white father” who has the Osages’ best interests lingering in his heart. Ernest treasures money and an easy life above all else, and he’s willing to do the unthinkable without any hesitation to get it. In other words (and to steal the title of a similarly themed masterpiece), there will be blood. Oh, yes, there will be blood indeed.

The historical aspect of all of this is the systematic destruction of the Osage by King and his like-minded followers. They marry the wealthiest members of the tribe, and through a series of accidents, unnatural “natural” deaths, and outright murders, they kill off as many of the natives as they can and leave all the headrights to every oil well in the hands of their Caucasian spouses. It is as abhorrently simple as that.

DiCaprio is at the center of all of this, and his performance ranks as one of the actor’s best. It’s a towering portrait of jittery cowardice and venal pride, with zero sugarcoating and no artifice whatsoever. DiCaprio strips himself naked and reveals levels of inhuman depravity that defy belief, which makes Ernest’s honestly heartfelt — and apparently authentic — embraces of Mollie all the more sadistically despicable.

But as great as DiCaprio is — and he is magnificent — the star is unquestionably Gladstone. While there were times I wanted the story to come more from Mollie’s point of view than it did, make no mistake: she is this epic’s heart and soul. Gladstone gives a titanic performance, one filled to the brim with restrained dexterity that enhances the emotional complexities of the drama. The actor made me feel things so deeply that there were instances when the snowballing, wretchedly engulfing pain became unbearable. And yet I remained frozen in my seat, eager to discover what Gladstone was preparing to show me next, her final moments with DiCaprio an explosively subtle sledgehammer of verbal and physical artistry that left me stunned.

This is not to say that Scorsese revels in the doom and gloom of this monstrous tragedy. There are moments of surprising levity sprinkled throughout, comedic bursts of ghoulish folly that only augment the terrifying reality of the carefully crafted, methodically sanctimonious, cold-blooded wrong being done to the Osages. When this house of cards collapses — and it must collapse, be certain of that — it does so because no one, not even King himself, is above letting their greed get the better of them and their self-perceived racial superiority cloud their judgment.

The technical aspects are unsurprisingly superb. The late Robbie Robertson’s final score for Scorsese (he’s previously composed for the filmmaker on The Color of Money, The King of Comedy, and The Irishman, and has been executive music producer on a variety of projects, including Gangs of New York and The Wolf of Wall Street) is sensational, a sonic whirlwind that quickly becomes the picture’s heartbeat. Director of photography Rodrigo Prieto (Brokeback Mountain) uses his camera like a weapon, staring straight into this never-ending darkness with an incisive, accusatory eye.

As for Scorsese’s longtime, not-so-secret weapon, editor Thelma Schoonmaker, the three-time Academy Award winner and eight-time nominee again manages the impossible. She cuts together this 205-minute beast into a fast-paced feast for the senses in which every moment feels essential and even the quietest scenes tingle with unparalleled electricity. As soon as the film was over, all I wanted to do was watch it again right there and then, my bladder be damned, and a big part of that is thanks to Schoonmaker’s editorial brilliance.

There is a point in Flowers of the Killer Moon where history, fiction, and revisionist reenactment collide, and it is a shocking and illuminating turn of events. In a flourish of bravado that would make Orson Welles rise from his grave and applaud, Scorsese shows how even the darkest chapters of history are transformed into easily digestible bursts of pop entertainment to be consumed by dull-eyed (or, in this case, dull-eared) masses who only want to revel in the salacious grotesquerie of it all and not deal with their lazy complicity, which has allowed massacres such as this to happen for untold generations, seemingly with no end in sight.

But then the director stops things cold in their tracks. The play-acting goes away. The façade is stripped bare. The wizard behind the curtain is shown as the charlatan he truly is. Scorsese gets the final word, and he holds nothing back. He looks the audience in the eye, daring us to turn away, knowing that if we do, then we’re not only willing to purposefully not learn from our rancid and racist history but, even more appallingly, we’re ready to forgive it, too.

– Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 4 (out of 4)