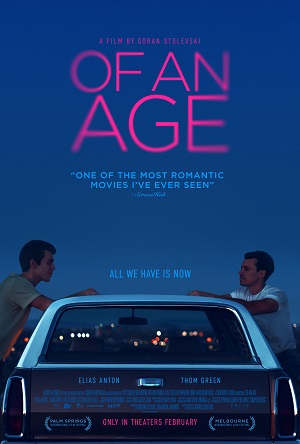

“Of an Age” – Interview with Goran Stolevski

by Sara Michelle Fetters - February 17th, 2023 - Features Interviews

Making Connections

Driving in cars with boys with Of an Age director Goran Stolevski

Filmmaker Goran Stolevski has followed up his striking, ethereally haunting feminist debut You Won’t Be Alone with the male-driven coming-of-age character study Of an Age, and the pair fit together beautifully. Where the former is a suspenseful 19th-century journey through witchcraft, identity, and humanity, the latter is a coming-out tale of a young Aussie immigrant grappling with his sexuality after a chance encounter with the Gay older brother of his best friend, circa 1999.

Both films are fascinated with self-exploration. Their main characters are learning who they are and figuring out who they want to be, with various individuals coming in and out of their lives and influencing their steps along the way. While fundamentally different in tone and execution, each still showcases Stolevski’s exquisite directorial confidence. This makes him a singular talent worth keeping an eye on.

Of an Age is split into two pieces. The first two-thirds takes place over the course of a day or so during the summer of 1999. After receiving a frantic call from best friend and dancing partner Ebony (Hattie Hook), 17-year-old Kol (Elias Anton) finds himself begging the girl’s older brother Adam (Thom Green) to give him a ride so they can rescue her from a beachside phone booth an hour outside Melbourne. Along the way, the pair make an instant connection, and this forces Kol to realize truths about himself he’s desperately been trying to suppress for far too long.

The remainder takes place roughly a decade later, but the less said about it, the better, as this final third should be experienced without any spoilers.

I sat down with Stolevski over Zoom to discuss Of an Age and how it compares to You Won’t Be Alone, and while we tried to avoid conversing about anything that should be left a mystery, there are a couple of instances where we do touch on a few key plot revelations. Keep that in mind before proceeding.

The following is the edited transcript of our brief conversation:

Sara Michelle Fetters: What I loved about You Won’t Be Alone and Of an Age is that they really do play very well together. They are these journeys of self: who we are, what we are, where we’re going. I’m imagining that this is a theme that’s important to you, this discovery of self.

Goran Stolevski: Yeah. In certain circumstances where you’re the outsider, where you can’t really quite fit into a community but you desperately want to connect. I keep pointing out: you could call this film You Won’t Be Alone as well, but that title’s taken. Loneliness and connection is sort of what I feel was the key crux of You Won’t Be Alone. People thought it was about claws. [laughs] But no. I feel it’s about belonging. With this one, I think a more interesting connection is what it’s really about as well.

I don’t insist on wanting to make films that are thematically related. I don’t have an ambition to be a classic auteur or whatever. I kind of go with what makes the chest bump most intensely. But [as for] both of these films, the previous one was my personality split in half between two women who happen to be witches in the 19th-century mountains, whereas this is clearly my personalities playing between these two kids in 1999.

SMF: With this one, you take a storytelling and creative leap of faith, in that you spend at least the first third, probably more than that, with two characters talking in a car.

GS: Yep.

SMF: From a directorial standpoint, that had to be challenging. From an acting standpoint, that had to be challenging. From a visual standpoint, that had to be challenging. And I’m sitting there watching the film, mesmerized. I can’t take my eyes off of it. How did you meet all of those challenges?

GS: If only I knew. [laughs]

That was one of the main things going in. The two main challenges or obstacles that I thought I would have, even before we cast it, [were] how you find a way to either have one person play 17 and 28 believably or find two people who can match the energy without interrupting that flow for an audience, and the other issue, for the first 16 or so minutes, it’s a certain kind of story, because it’s taking place from a certain kind of emotional reality and state of mind.

But then there’s a shift. The shift comes from a certain place, because, to me, the first minutes [are] how day-to-day life feels for this kid, and that’s how adolescence felt for me. There’s that tearing of the universe, where that day-to-day is just kind of suspended, and [then] there’s this thing, this event that just changes you, and you don’t even realize it’s changing you in real time.

That’s all lovely to talk about theoretically and directorially, but having an audience get used to this kind of pacing and energy, only to suddenly shift and you’re driving slowly and talking slowly,… [is] a really strange thing. I mean, “leap of faith” describes it.

When we were shooting, we had two cameras running, and we were watching. The first proper take we did of that scene was 32 minutes. They were driving in a loop. I’m lying back in the back seat so that I’m not visible with the double monitor, and the two guys are in the car. The three of us are kind of alone, and then there’s no other cars around us for safety.

We just forgot that the world existed, that time existed. For 32 minutes, [Elias and Thom] would look back and forth, improvise, do the lines as written, whatever they felt. There wasn’t a cut. I would maybe chip in if there was a silence to make a suggestion, but that was it. The only way we know it was 32 minutes is because the battery [in the camera] ran out, and we had made the full loop. [laughs]

But to us, it felt like three minutes. You forgot that it wasn’t reality.

SMF: When did you know that Thom and Elias could pull this off?

GS: I was very confident, partly based on the options I had. There was no backup. [laughs] There were a couple of other interesting kids whose acting I liked that I will definitely work with on a different film. But in terms of people who fit these roles and could believably have chemistry with each other, I was confident this was as good as it was going to get. I thought, if it doesn’t work with [Elias and Thom], maybe the problem was me, maybe it was the writing. Something is there or it isn’t there. But if there isn’t something there, it’s not the fault of the actors.

We didn’t do rehearsals beforehand, but we spent a lot of time together just connecting. I would talk through the script, so they knew what my intention in writing every single line was. They were aware of where it came from, so that if they changed anything — and they had the freedom to change it or delete it — they knew where it was coming from.

The first day, we did a test scene together, and it was already electric. The first scene we shot was the first time before Kol vomits. It’s a different energy, and it played out very different to what I thought it would in terms of how I wrote it. But from those first takes, it still felt like, yeah, this is a movie. This is the movie I wanted. I wanted to watch more. These actors were the best possible gift you could have as a filmmaker.

SMF: I love that you talk about that moment with the vomit. I mean, it is icky, I’m not going to lie. It’s vomit. It’s gross.

GS: Right. I’m also extremely squeamish. No one believes me, but I am. [laughs]

SMF: Wow. After your last movie?

GS: Yep.

SMF: I’d never have guessed, based on that one. Anyhow, the reason that I like that scene is that that moment is there is because of what Kol is dealing with. It’s hinted at, and it’s not difficult to put one and one together as far as what his journey is and what he’s going through. But to be in that moment where somebody tells you something and you realize it’s your truth at the same time? I mean, he’s not making a judgment. He’s realizing something about himself and it’s difficult. Or, at least, that’s how I took it.

GS: I’m honestly not sure. I think there’s the unconscious realization. That’s the panic of it. In my case, I didn’t meet a Gay person in real life until after I was openly Gay. I was the only Gay in the village.

Even after I came out, no boy told me any secrets. I lived in the studious, most boring part of Melbourne. I think it’s like, if you are a Gay human being, you just spontaneously combust rather than live there by choice.

Anyway, I somehow got stuck there in Melbourne. The closest I can think of in my own life in terms of seeing a Gay character, it was in a film. I grew up in a lot of art house cinemas, so just an attractive man taking his shirt off? I’d be like, why am I having these feelings? They would make me angry. I was still in denial.

There is a panic that comes across in those moments. And how dare someone even imply it, right? There’s a semiconscious thing where you know, but there’s also an active denial. I think, in that moment when he finds out for sure, it’s that part — the active denial — taking hold. But it’s immediately followed by an element of trying to be totally cool with this. There’s a gradual reset in the story, where it starts all over again, and, as an audience, you’re processing these feelings in real time.

I think that moment came from me imagining “what if.” Not when I was 17 — I was already militant. But at 13? At 14, when I was just as Gay but in deep denial and had grown up with homophobia, not as a type of prejudice but as the only reality that exists? How would I have coped? That moment felt natural.

It took me ages to realize how much of my brain was really stuck in a binary system, quite female, and how much of that I had to suppress later on. When I was five, I used to play with dolls and that didn’t get in my way. But at some point, I learned we don’t want to get beaten up playing with dolls. And so on and so forth. That instinct takes over.

But I wasn’t interested in dwelling on the negative. I think anyone who would watch this film is already educated about how oppression existed for Queers in 1999. I’m not going to teach anything in that sense.

But let’s start over. There’s a special kind of loneliness for a Queer kid, even to this day, but even more so in the analog era, where you couldn’t use your phone to connect with a stranger somewhere far away. The flip side of that is that if you found that someone else who’s Queer, there’s an electricity that is irreplaceable. There’s a point of you being the only two people in a room who have this secret. It’s super fucking sexy but also super poignant. You get to experience that as a Queer person.

I didn’t experience it in that way when I was younger, but later on, there were moments of that, where I felt circumstances were forcing me to not be open with my then boyfriend, now husband, in terms of our connection. I was like, we have something and there’s an electricity in knowing that. The fact that I have something that only he and I know about, it’s hot and it’s joyous. When you know real loneliness, overcoming it is so much more poignant.

With this story, I was trying to kind of find that romantically transporting, fulfilling element. I wanted these characters to make the most of their moment.

SMF: Before we go, what do you want audiences to take away from watching the film? What do you hope that they’re talking about afterward?

GS: People come up to me and go, “How did you know my life?” And a lot of them are men, but a lot of them are straight women too. I love that I can connect with people who are so fucking different from me through this story. I wrote it not assuming anyone would ever be interested. My husband read it and he cried, but he knows me. Then my producer read it, and she cried. I was like, she knows me, too, but she’s also a straight woman.

I just want these feelings I write about to keep connecting with someone, anyone else. That’s all I could ever ask for in life.

– Interview reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle