“The Outpost” – Interview with Rod Lurie

by Sara Michelle Fetters - July 2nd, 2020 - Interviews

Under Fire

Director Rod Lurie on bringing the story of The Outpost to life

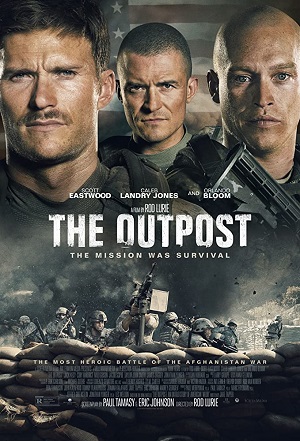

Based on the best-selling book by journalist Jake Tapper, The Outpost chronicles the 2009 assault on Combat Outpost Keating in Afghanistan. Located at the base of the Hindu Kush Mountains just 14 miles from the Pakistani border, 53 soldiers fought to defend themselves against an overwhelming force of more than 400 Taliban fighters. It is still considered to be one of the deadliest fights of the Afghan War. More importantly, it’s a fight that never should have taken place.

Veteran director Rod Lurie’s adaptation goes into great detail as it analyzes the men stationed at Combat Outpost Keating and the building dread most of them felt knowing that an assault on their indefensible position could happen at any time. Seen entirely through their eyes, the film is a visceral powder keg that explodes with devastating emotional ferocity once the attack on the outpost ultimately begins.

Featuring several unforgettable moments and showcasing a performance from actor Caleb Landry Jones that is arguably the best of his career, The Outpost moved me in a number of unexpectedly intimate ways. I had the pleasure to sit down and chat with Lurie over the phone about his film and his career for a good half-hour. Here are some slightly edited excerpts from our wide-ranging conversation:

Sara Michelle Fetters: I guess I should start with the basic question of, at what point did you get Jake Tapper’s book? When did you know that this was a film that you wanted to make?

Rod Lurie: They came to me. This movie was originally going to be directed by Sam Raimi. He had the rights to the book and he had the rights to a screenplay that had been written by Paul Tamasy and Eric Johnson. But for his own reasons, Sam decided to drop out of directing the film.

I was approached but couldn’t make it at the time. But a couple years later it circled back to me. I’d heard that this company called Millennium, who mostly had done these shoot ‘em ups, like Rambo and The Expendables, was interested in making this film. They wanted to take the company into the directions of more artful films and they were ready to go with The Outpost. From that point, we started making offers to actors, and by the fall of 2018 we were shooting.

Sara Michelle Fetters: It’s interesting for me to look at this film and compare it to the majority of your filmography. With most of your films, you have written most of them yourself and by and large they are far more intimate as far as how many characters they are dealing with. When you look at this project, I mean, you’ve got 50-plus soldiers that you have to keep track of.

Rod Lurie: My other film this size probably was The Last Castle, which also had a military bent to it.

When I write films, I tend to write films that can get made. I don’t write $100-million films because it’s typically difficult to get those made. It’s also difficult to get small ones made, but you’ve got maybe a better shot.

I’ve been interested all my life in intimate topics. Most of them political and most of them dealing with feminist issues. But this story was really important to me because I was in the military and I love my fellow soldiers. I love them more than I love the military.

One of the things about this story is that most of the Afghanistan war films deal with Navy Seals or they deal with Rangers or they deal with Special Forces. This story was about regular dudes. Guys who are not necessarily career military. The military was a stopgap for these men as they continued on with their lives, and they were caught in this terrible situation. I thought that was very interesting. I’m making a movie about people you don’t make movies about. That’s exciting.

Sara Michelle Fetters: One of the more fascinating aspects of the film for me was that I truly felt like I’d went to school with these guys. You look at the soldier Caleb Landry Jones is playing, Ty Carter, I swear I went to high school with that kid. I could see him there. Remember everything about him.

This made his reaction to Combat Outpost Keating hit home for me in a very personal way. I knew what his reaction would be. I feel like mine would have been very similar. How was this even possible? How did the U.S. Military think putting Keating where they did was ever a good idea?

Rod Lurie: That’s absolutely true. It was a tactically disastrous decision. They had their reasons, but the reasons were not good enough to justify having done this. In fact, the guy who decided to create these outposts was a colonel, his name was Mick Nicholson. Nicholson was my squad leader when I was at West Point. He was the guy who hazed me relentlessly, even though he was a complete stud at West Point. Now he’s a four-star general.

So, he’s a great, great soldier. No question. But this was unquestionably a bad decision.

It’s interesting when you’re talking about the guys that you went to school with. The nature of the war is that you have all of these various personalities coming from all over the country with different political beliefs, different religious beliefs, different sports beliefs, different everything, and they all have to work together. They’re all different human beings with very different upbringings.

I think it the most successful war-based films, these differences are an essential aspect of the storytelling. I looked at a movie like Platoon which very successfully shows the variations of these characters and we tried to do something similar. These guys should have felt like people you knew in high school. I’m glad you felt that way.

Sara Michelle Fetters: There’s a moment in the movie that I don’t want to talk too much about because I think it’s a bit of a spoiler, but there’s a montage of a number of the soldiers on a SAT phone speaking to their families, saying what they can but not being able to tell them what they truly want them to know.

Rod Lurie: What they’re trying to express is their sense of love for their families. They want to get that across because that’s the moment in the film where they think that they’re going to close down the base. But they also know that by closing down the base that might incite the Taliban to attack them. They don’t know what’s in their immediate future.

Your instinct, I think, is to reach out to people that you love. If you were on a plane and the plane is going down, and you still had your phone, no doubt you’re going to call your husband or your wife or your children or your parents and tell them that you love them. That’s human nature.

That sort of was the sense that we had for that sequence. They all react differently. They all behave differently. Some can’t help but continue to fight with their loved ones. Some just say, “I love you.” One person just wants to make clear he’s going to quit smoking. I’m glad you pointed out that sequence. I’m very proud of it.

Sara Michelle Fetters: As you should be.

I was curious what instruction you gave the actors. As you say, each of them reacts differently on these calls. All of their conversations are different. It almost feels like you just let them go off script, but I have trouble believing you actually let them improvise.

Rod Lurie: No. You are correct. Every one of those conversations was improv. All of those actors, they were in communication with the families of the people that they were playing. They got to know who each of these men was on a very personal level. This was extremely helpful. You’re hearing these stories about each man from the point of view of a family member who knew them best.

So, for example, the guy playing Kevin Thomson [Bobby Lockwood], a private, knew that he never did speak to his mom. So he gets on the phone and decides he can’t speak. The guy playing Sergeant Gallegos [Jacob Scipio], he always fought with his wife, they always fought, no matter what, so he knew that they would fight and that would be the way that they would say that they loved each other.

The actors got to know their families, and so that concentrated itself into that one sequence. I think it did so rather well.

Sara Michelle Fetters: One of the reasons I think this moment worked so well for me is that, for the first half of the film, I was admittedly worried I wasn’t going to be able to keep track of who all of these men were. There is so much exposition that is required to flesh out, not only who these characters are, but the geography of Keating itself, and it didn’t occur to me until that moment that you’d done a terrific job setting all of that up.

Rod Lurie: Right. Thank you. One of the curses of the military film is that most people have got very short hair. Nobody has facial hair. They’re often wearing helmets. They’re often wearing enough gear that you can’t even make out their body shape. When you look at a film like Black Hawk Down, as much of a masterpiece as I think it is, the most common complaint about the film was you couldn’t tell anybody from anybody else. If you think about it, Orlando Bloom looks a little bit like Josh Hartnett, who looks a little bit like Eric Bana.

One of the things we sought to do was, through behavior more than anything else, differentiate the characters. One guy is a wise-ass. Another guy is an asshole. And another guy is so unathletic. So on. So forth. We wanted to ensure that these behaviors were true to who these men really were. We wanted to honor them by being authentic. Additionally, we also tried to give all the characters one big moment where they stood out and were the center of the scene. I think that was helpful as well.

Sara Michelle Fetters: Going back to that geography, it’s pivotal that we understand the layout and where everything is at Keating, otherwise that last hour is going to make no sense from a visual perspective. What were the difficulties involved in ensuring that the audience could learn that geography?

Rod Lurie: You’d make a good director because you identify the problems that we needed to solve ahead of time. [laughs]

That was an issue that had to be really crystallized. These were 54 men, 53 in the battle, who were trapped in a base at the bottom of the Hindu Kush Mountains. It was inevitable that they were going to be overrun because they didn’t have the high ground. They were just literally, to use a cliché, sitting ducks.

One of the things we had to do in the first hour of the film is to reinforce over and over and over again was how they are at the base these mountains. There are many shots of the men looking up into the mountains, and even ones where they are making a point of where they are geographically and why it is they are there.

I also made a point of taking a squad up into the mountains and looking down at the base so that we could see from that point of view, visualize what the enemy would see. I needed the audience to know how easy it would be to attack the base.

Most importantly, there are three times in the movie where sort of tours of the base are taken. Here’s where the command building is. Here’s where the mess hall is. Here is where the mortar pit is. By the time we get to that second hour, you should know the outpost as well as the soldiers do.

Sara Michelle Fetters: You have mentioned in the past in other interviews how your films attempt to be apolitical in how they attack their subject matter but that it always seems like your harshest critics always seem to come from the Right.

Rod Lurie: Right. Correct.

Sara Michelle Fetters: Why do you think that is?

Rod Lurie: Well, okay. Let’s be fair for one second. I am not apolitical. If I ever said that my films come from an apolitical point of view than I wasn’t telling the whole truth because I do think they come from a political point of view.

I’ll work my way up to The Outpost, which is apolitical, but The Contender, a small movie I made in 2000, was absolutely coming from a pro-Left, pro-liberal, point of view, and the Right absolutely eviscerated me. I remember a review from Michael Medved that was much more a political screed than it was an artistic screed against me. Another movie of mine, Straw Dogs, that was made in response to the rightwing nature of Sam Peckinpah’s film. I wanted to see if I could make a film that told exactly the same story but from a leftwing perspective.

Now, you come to a movie like The Outpost, and one of the things that I’m proudest of is the fact that when we did our research screening and one of the questions we asked the audience members was, does this movie have a political point of view, the answer was unanimous. And by unanimous, I mean that unambiguously and without equivocation 100% of the people said it wasn’t a political film. They did not find a political message one way or another. This is purely a story about these guys and what they had to go through, and it tells the story objectively. There might be a criticism of the military in there, but remember that this base existed through both the Bush and Obama administrations.

So, going back to your original question, why did they come after me in the past from the Right? Because I was on the Left, and that was perfectly fine with me.

I’ll tell you a quick anecdote. The Contender is a political film about a female Senator who comes under a scandal played by Joan Allen. There’s a point in the film where she gives a speech before Congress. I shot it dry without music. Steven Spielberg buys the movie for DreamWorks and we sit in the editing room, and he says, “This would be a great scene to have music in.” And I said, “But Steven, if I put music there it’s as if I’m endorsing what she is saying politically.” And he responds, “Right. It is your movie. You’re allowed to have a point of view. This is not a news show. You can endorse what she’s saying if you want to endorse what she’s saying.” We put music in that scene, and it worked magnificently.

So, my past films, they definitely presented a point of view, and I will do more of those films in the future. But that’s not the point of The Outpost.

Sara Michelle Fetters: Off topic, but I’m going to say that as much as I love Julia Roberts in Erin Brockovich, I would have given the Oscar that year to Joan. I thought that was easily my favorite performance out of the five nominees that year.

Rod Lurie: Thank you! I couldn’t agree with you more. We had really hoped that Joan had a shot and, of course, I don’t know where she placed. But I know it’s a beloved role for her, so that means a lot. But, yeah, I thought Julia was great and all, but to me it was Joan all the way. She’s a great actor. A really great actor.

Sara Michelle Fetters: Speaking of great actors…do we get to finally retire this notion that Caleb Landry Jones is a one-note actor? I’d thought after the trifecta of Get Out, The Florida Project and Three Billboards we were finished with that, but apparently there are those who for whatever reason feel the need to keep that going. He’s extraordinary here.

Rod Lurie: I think that we can, retire that conversation, and I’ll tell you that the role that he plays here as Ty Carter, I’m really hoping that the Academy remembers him at year’s end. It’s going to be tough, I admit that, but he’s just wonderful in the film.

When I first met Caleb, I met him at Mel’s Drive-In in Hollywood. He had long, stringy hair and he was really skinny. He reminded me of Brad Pitt in True Romance. [laughs] When you’re speaking to him, you’re not inspired with confidence because he sort of rambles on. But he’s such a great actor, and when he tells you, “No man, I can do this. I can pull this off. I can be a Marine,” you believe him.

I sent him to go visit the real Ty Carter and Ty calls me and he says, “Rod, is Caleb going to go to the gym?” And you know what? Caleb went to the gym. Caleb did the training. Caleb was so invested in this part. He was the stud of basic training.

I’ll tell you something that’s not well known, and that is that Caleb’s brother is a Marine who lost both his legs in Iraq. He read the script and told Caleb, “You’re going to make this movie.” He had no choice in the matter. Caleb’s brother came to Bulgaria and made sure that he was holding his weapon right, even though that was the job of our technical experts. That was something to behold. It gave me chills.

Sara Michelle Fetters: Speaking of those technical experts, we had a little back-and-forth on Twitter where you mentioned you had soldiers from Combat Outpost Keating on-set with you. What was that like for them?

Rod Lurie: It was brutal for them, no lie, but it was also beautiful. There was a catharsis, I think, but everybody, all of those soldiers, all of the crew, we were all in tears at some point on that set. We had Dr. Cordova on the set, and he was there on the day that we shot the operation scene, which was probably one of the most profound moments of the doctor’s life, and he just had to walk away. He helped us get everything ready and then he had to walk away. He couldn’t be there.

Daniel Rodriguez plays himself, and he had to replicate the death of his best friend. That was an incredibly emotional moment, let me tell you. And Carter, who suffers from PTSD, one day during prep he stepped on a garden hose and it made a loud bang sound. He went immediately down to the ground. They were all in some ways reliving their personal experiences because Eric Carlson, our production designer, had done such a brilliant job of recreating Keating.

Sara Michelle Fetters: With the world we live in right now, it’s sadly no surprise for me to admit I watched your film via a screening link. When they sent that over, they also included a letter from you. It basically said, in no uncertain terms, to play the film loud and on the biggest screen possible.

I only bring this up because I think, looking at your filmography, no matter how intimate your films are, they are shot, constructed and sound designed so that the audience has that big screen, intimately immersive experience. All of them, this one maybe most of all. We are unfortunately living in a world right now where that’s not entirely possible. What is that like for you as a filmmaker? It has to be frustrating.

Rod Lurie: It absolutely sucks. No question. It sucks. I designed this movie for the big screen. I shot it in scope for the big screen. The sound design is so intricate. It’s designed to be in not just theaters, but in theaters with the Atmos system. When you learn that 99% of people are going to see this movie at home, it’s a little disappointing.

However, the reports I’ve been getting is that it plays extremely well at home. If you’ve got a good system, you’ll be in really, really good shape. But, yes, play it loud. Very loud.

I will tell you, Sara, from now on whenever somebody makes a film that’s not James Bond or not a superhero film, you kind of have to assume that it’s going to be a VOD movie. That people are going to be watching it at home. That’s the way it’s going to go from now on.

I think people are becoming accustomed to seeing these movies at home, and I think it’s going to stay that way. I’ve got several projects I’m getting ready, and I don’t know which will go next, but I’m assuming that they’re not going to be in theaters. You have to make that assumption, and so I think you have to take that into account when you make a film now. That’s really too bad. But it’s also reality.

Sara Michelle Fetters: You were a film critic before you became a filmmaker, and I’m sure you would agree with me that our second home is the movie theater. We all adore, at least I hope we adore, the theatrical experience. And yet, we just got notified by the local publicity company that they are in the process of maybe restarting some press screenings, and they asked what we would think about that. I admit there is some hesitation at the moment on my part, and I know I’m not the only one feeling that way. What do you say about that? Is that understandable?

Rod Lurie: Unfortunately, it is understandable. It’s something everyone has to think about.

With this film, we did try and set some press screenings. There were some cities where we were able to have screening rooms, including LA, but there were just no takers, and I get it. Definitely.

Hopefully the theaters that are showing The Outpost, I think they’re going to be in the safer areas of the country. But I only want people to go if they feel comfortable and if their healthcare specialists are giving them the go-ahead. Otherwise, stay home. Watch it at home.

But you are right. The theatrical experience is not just wonderful from the point of view of how you see a movie, but also the community of emotion that surrounds you while you’re watching it. What’s more fun than going to a great comedy? We all laugh at the same time. It’s just amazing. Or we all leap at the same time because the head comes out of the boat in Jaws or when Glenn Close comes alive at the end of Fatal Attraction. These are just these fantastic moments, and it’s a shame that a lot of that is going to literally just disappear. It’s really too bad.

Sara Michelle Fetters: Do you think The Outpost is saying anything in regards to what is currently going on in Afghanistan?

Rod Lurie: As I said earlier, I don’t think the movie has any sort of political point of view. It really does center on this one event. I will tell you that I think this movie says a lot about the American soldier. About the gut-level instincts that exist within the American men and women that serve in the military.

Yes, I’m a liberal, but I’m also very much military, and there are a lot of people in the military that are liberal or will vote Democrat. But in the end, when you’re in the field, you don’t give two shits about how somebody voted when they’re carrying you across an outpost after your leg has been blown off. You don’t care. You just want to know that they’re there to carry you. If you see one of your guys under fire, you’re not going to say f-you, you voted for Trump, I’m not going to protect you. No. You save their asses. That’s what it boils down to. That is the spirit of the American soldier.

– Portions of this interview reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle