Unforgettables: Cinematic Milestones #26 – Seven Days in May (1964)

by Sara Michelle Fetters - March 20th, 2024 - Features

Six decades later, Seven Days in May remains a powerfully prescient political thriller

NOTE: This feature originally appeared in the February 23, 2024 edition of the Seattle Gay News.

Of the seven motion pictures Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas starred in together during their careers, 1964’s Seven Days in May is unquestionably my favorite. The 1957 Wyatt Earp/Doc Holiday Western Gunfight at the O.K. Corral is probably their most fondly remembered, and the rambunctious 1959 American Revolution satire The Devil’s Disciple (featuring a memorably droll Laurence Olivier as British general John Burgoyne) is also a minor classic I’m particularly fond of.

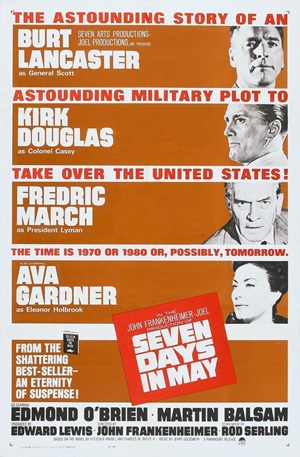

But this John Frankenheimer political thriller — based on the best-selling novel by Fletcher Knebel and Charles W. Bailey II, featuring a crackerjack screenplay by Rod Serling and an all-star ensemble that includes Fredric March, Ava Gardner, Martin Balsam, Richard Anderson, Andrew Duggan, John Houseman, and an Oscar-nominated Edmond O’Brien — sizzles, building to a power-packed conclusion that’s breathless in its sensationalism and terrifying in its prescient accuracy.

Why prescient? The first time I watched this marvel was during the 1998 Clinton impeachment proceedings. While this wasn’t a military coup, I still found it striking how the Republican House majority would try to usurp power in such a blatantly antidemocratic fashion. It was surreal seeing how artistic imagination was not so much mirroring Washington, DC, politics as it was echoing an honest-to-goodness political reality 34 years later.

If that was a nifty bit of unintentional Carnac the Magnificent–style precognition, what’s going on right now borders on Rasputin territory. Six decades after Seven Days in May made its theatrical debut, the US is entering a new presidential election cycle in which the leading Republican contender is facing 91 indictments and four separate criminal trials, had a New York judge order him to pay $355 million for fraudulent business practices, and has seen a jury find him liable for sexual abuse and defamation of a journalist. He’s also openly stated he’d be a “dictator for a day” if re-elected and hinted that judges he elevated to their current position on the federal bench should be ruling in his favor, even when the law clearly goes against him.

Suffice it to say, Frankenheimer’s unnerving spellbinder hits even harder in 2024 than it did in 1964. But while that should be impressive by itself, it also wouldn’t matter if the filmmaking wasn’t so memorably beyond reproach. In a career that includes certified stunners like Birdman of Alcatraz, The Manchurian Candidate, The Train, Seconds, Grand Prix, and Ronin, this drama sits comfortably alongside them all. Frankenheimer’s direction is cool, precise, and tinged with paranoiac uncertainty. This is some of his best work.

As labyrinthine as things become, the core plot is honestly fairly simple. A series of unusual coincidences lead Col. Martin “Jiggs” Casey (Douglas) to believe that his superior officer Gen. James Mattoon Scott (Lancaster) is planning a military coup. Scott and his supporters among the Joint Chiefs of Staff believe President Jordan Lyman (March) is entering into a treasonous treaty with the Russians they think will cripple the US nuclear advantage. This is reason enough for all of them to remove the president from power.

While Jiggs also is no fan of the treaty, he does believe in the Constitution, along with his oath to protect it. Lyman tasks him and other members of his staff to definitively find out if Scott truly is making a play to overthrow the government, and they only have a week to suss out the truth. It’s a ticking-clock race hurtling toward unimaginable disaster, culminating in a verbally intense face-off between Lyman and Scott that’s one of the best I’ve ever seen.

There are subplots galore. In one of them, Jiggs visits Eleanor Holbrook (Gardner). She’s a DC socialite who shares an intimate past with Scott, documented in a series of salacious letters written by the general that would cause a scandalous maelstrom if they saw the light of day. Douglas and Gardner ignite the screen as Jiggs struggles with his conscience and Eleanor slowly realizes the real reason for her friend’s early evening surprise visit.

Another involves perennially inebriated Sen. Raymond Clark (O’Brien), who investigates a secret military base supposedly hidden in the vast nothingness of Texas. O’Brien gives a towering, complexly wounded performance. Sen. Clark is reborn during his trek, and his rediscovery of an interior resolve and love of country sparks something powerful deep inside of him. The actor balances comedy, tragedy, heroism, and ineptitude with carnal gravitas, and in a career of superlative supporting performances (which includes a Best Supporting Actor Academy Award a decade earlier for The Barefoot Contessa), to my mind, this one towers above them all.

Yet it is that climactic showdown between Lancaster and March, each delivering body blow after body blow, that after all these decades still packs the deadliest punch. Scott and Lyman intellectually duel, going over the events of the past week, along with the potential earthquake that could be triggered by their actions (or inactions) the very next day, as the democratic fate of an unknowing nation hangs in the balance. It’s a stunning master class of emotional nuance, and Frankenheimer, cinematographer Ellsworth Fredericks, and editor Ferris Webster all know better than to get in either man’s way.

The thing is, every item that Scott and Lyman are heatedly debating could be inserted into political discussions taking place this very second, and I doubt anyone would bat an eye. The difference? In this film, the president takes the moral high road, deciding not to get into the mud, even if doing so would almost certainly bring his opponent to his knees. As for General Scott, while he does spout platitudes and twists constitutional dogma to suit his needs, he also keeps his line of attack closely mirrored to the underlying truths of what the treaty with the Russians does and does not do. This is a man who has no need of “alternative facts” to make his case.

That’s the scariest thing about Seven Days in May. Serling took great liberties with Knebel and Bailey’s source material, and it’s clear The Twilight Zone creator was not above inserting the fantastical if it helped hammer home his thematic point about disquieting, unthinkable future possibilities. But even if he foresaw the power that unscrupulous television personalities could wield and how their form of propaganda could pass from one viewer to the next like an unstoppable (and invisible) virus, he still posited that fact would always trump fiction, and that those with power would rather wield the former than dirty their hands by sifting through the latter.

If only that were the case.

Celebrating its 60th anniversary, Seven Days in May is available on DVD and Blu-ray, and can be purchased digitally on multiple platforms. It is currently streaming on Tubi.