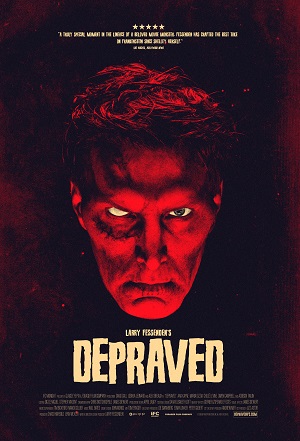

“Depraved” – Interview with Larry Fessenden

by Sara Michelle Fetters - September 18th, 2019 - Interviews

Depraved Monster Magic

Larry Fessenden on Frankenstein, video stores, Milicent Patrick, damaging the patriarchy, Get Out, feminist filmmaking and the enduring strength of human decency

Back in college I used to manage a small neighborhood Seattle video store. While we’d never be able to compete with any of the chains (i.e. Blockbuster) or have the same sort of massively extensive library as Scarecrow Video (now a nonprofit boasting the world’s largest cinematic inventory of more than 130,000 films) our little shop still managed to hold its own. I made it a point to bring in as many timeless classics, independent curiosities and international titles as our budget would allow, and as such we generated a sizeable following of dedicated renters who helped us make sure we remained financially afloat.

What does this have to do with vaunted indie horror auteur Larry Fessenden and his latest bag of grisly, character-driven tricks Depraved? During the early 2000s two of my go-to off the beaten path genre offerings I’d constantly recommend to people looking for something unsettlingly different were the filmmakers grungy 1995 vampire shocker Habit and his austere 2001 minimalistic monster flick Wendigo. While not for all tastes, I usually knew just exactly who to suggest these creepy cult favorites to, and more often than not renters would return each film excitedly wanting to discuss their favorite scenes and moments.

“Oh, my God,” exclaims an excited Fessenden. “That’s fantastic. It’s so great to hear and I really appreciate it. I’m so sentimental about video stores. It used to be where I would go if I had writer’s block or just wanted to get out of the house. I’d go to King’s Video in New York City and just wander the aisles and drink in the whole history of cinema without having to spend a dime.”

I was chatting with the filmmaker over the phone about Depraved, his marvelous 21st century take Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein story. In this version of the tale, Adam (Alex Breaux) wakes up with no memory of who he is, why his body is covered in several strange, gruesome scars or where it is he’s currently living. Turns out, he’s in a secluded New York City loft, and he is there with doctor, scientist and former Army medic Henry (David Call). The doctor has been treating Adam, and in a few short months he teaches his patient how to speak, helps him regain his strength and slowly nurses him to something reasonably close to full health. This treatment is funded by wealthy pharmaceutical businessman Polidori (Joshua Leonard), a selfish egotist and libertine who treats Adam more as a piece of property than he does a flesh and blood human being.

The reason our video store conversation mattered was in large part because home video is a big reason Fessenden currently has the career he does now. Films like Habit and Wendigo, while given minor theatrical releases, truly found their audiences thanks in large part to being readily available for rental at those stores. “Video stores were such a great thing to have in your local neighborhood,” muses the filmmaker. “They really helped make my career. My films didn’t necessarily get the wide theatrical release or all of the attention that they maybe deserved. Yet they grew, especially in the case of Habit, these large cult followings because people found them at their various local video stores.

“I eventually got a good indie distributor, Fox Lorber, and Habit just seemed to make it out there. It was in Blockbuster. It was in the local mom and pop store. It was everywhere, and that was fun, which is funny because I hated the cover. I didn’t know why they put me on the cover instead of the girl, the vampire lady. But in the end, now I’m very fond of it [the cover] because it’s just my big-ass face all smeared green. People would rent that movie in large part because of my green big-ass face. How can you not love that?

In the future, the kids that ended up working with me and becoming my comrades? It’s all because they had picked up those videos in Maryland when they were literally high schoolers. It’s a great legacy.”

Fessenden pauses for a moment before continuing. “You’ll not discover my films now in the streaming environment,” he states winsomely. “You have to really look for them, and I think that’s unfortunate. We’ve lost something for sure.”

Not that the filmmaker’s works aren’t available on Blu-ray. Four of his most popular films, No Telling, Habit, Wendigo and The Last Winter, got their own four-disc collection chockfull of special features from Shout! Factory genre label Scream! Factory in 2015. “I made that happen,” he laughs proudly. “Over the years, I got it so that IFC owned all my films. I then took them to Shout! Factory and said, don’t you think that I should have a box set? The funny thing is that now IFC works with Shout! Factory on all their releases. So I, kind of inadvertently, but also kind of intentionally, set up a relationship that’s worked for both companies.

“To be honest, I was determined to sell Depraved to IFC. I went through sort of a very circuitous route so this could potentially happen, but eventually they bought it. So now all my movies are still under one roof and maybe, just maybe, I’ll have another box set collection sometime in the near future.”

As for Depraved, it’s no secret this is a project Fessenden has been intermittently been working on for over 15 years. “I found a one-page summary of the movie on the computer from December 2, 2003,” he says nonchalantly. “I think that’s how far back it goes, which doesn’t mean I tried every day for the next 16 years to get the film made. I didn’t. But I did work on it on and off. I had a lot of distractions, and that’s one of my problems, but it was always a story I was interested in seeing get made.

“I think one of the primary problems I was having was that I was trying to cast it like a more significant film with a movie star. That it would be interesting to see a star in a lower budget, down-and-dirty modern Frankenstein story. Had I gone that route it also would have led to more significant financing. But it never worked out.

“So, after about ten years, I decided to make the film with the people I was currently working with. I’ve been producing very low-budget movies and getting a lot of careers underway, and I had a great crew of talented, dedicated artisans available to me. I just said to them all, guys, let’s do my movie now because I can’t wait any longer for the industry to pay me some attention.”

I can hear his grin through the phone as he makes that last statement, a hearty mischievous chuckle escaping his lips. This makes it clear just how much making this film meant to Fessenden. Even more importantly, it also hammers home just how essential it is he finds Mary Shelley’s source material and just how timeless a story he believes her Frankenstein to be.

“It’s one of the great pieces of literature,” he proclaims emphatically. “We missed the 200th anniversary by a year. I mean, technically I made it during the anniversary, and that’s maybe even more poignant. But in any case, I do sort of wish I had made Depraved a year prior so it would have been released on that anniversary. You can’t have everything, I guess.

“It’s funny. A lot of people now realize that Frankenstein was written by a young woman, but because of that anniversary a number of people now know more about the origin story. It really is amazing, especially in the #MeToo years to think about the insight Shelley had in writing her book and the condescension she had to deal with from the people who published and read it. Everybody thought her fantastic husband had written it. To disprove them and prove she wrote it herself she came up with the cover story that she came up with the tale in a dream because no one would believe that a woman would be able to just have this incredible flight of imagination. It would have to have been like sort of handed to her from the heavens or something. In some ways all of that is such a great origin to this fantastic story, a story that can now never be taken away from Mary Shelley. It’s hers, and it always will be.”

For his take on the material, Fessenden felt the key to making the story work for the modern age was to tell things almost entirely from the creature’s point of view. Adam is the central figure of the tale and it is via his eyes that viewers obtain a full understanding of the world he has awoken in and the people, primarily Henry (his creator) and Polidori (his financier), whom he ends up interacting with. “I wanted to tell the story from the monster’s point of view because we always see him as an ‘other,’” explains the director. “Even if he’s sympathetic all the way back to Karloff, and you can see that he’s in agony and feels alone, you still see him as a monster and as a strange aberration. I thought, what would it be like to wake up and be the monster?

“We can all relate to feeling like an outsider. I would say that almost every kid growing up they feel like they’re being bullied or misunderstood, and that’s becoming more and more acute in the conversations we’re having nowadays with identity politics and all that goes along with that. I wanted to explore that along with the bewilderment of life, which I think is something we all feel, and would be acute if you just woke up in full adult body and didn’t know what had brought you here. On top of that then you are haunted by these memories of a life you don’t remember ever actually living. How terrifying would that be?”

One of the primary changes to Shelley’s story deals with how Henry and Polidori end up with Adam’s brain. Unlike a diseased or damaged brain, their creature gets a healthy one courtesy of a young, unwilling donor. “It’s so traumatic, isn’t it?” asks Fessenden. “It’s so profound. So sad. I love the moment where this young kid played by Owen Campbell says, ‘I’m just going to leave, but don’t worry. We’ve got tomorrow.’ And it’s the story about maybe you don’t have tomorrow and how terrifying that is.

“That’s one of the things that draws me to horror, this kind of gentle reminder to the viewer that you don’t know what’s in store and life is very precious. It’s really a movie about that. He goes out only to wake up in this bewildering place which just so happens to be the body of the creature, Adam. He can’t figure out who he is but he knows he loved this other person, he’s just not initially sure who that person was or if she even existed in the first place. Was she just some he made up? Was she a fantasy? He doesn’t know, mainly because he doesn’t know who he is himself. It’s all fragmented, but he’s determined to figure that out.

Then the tragedy of being the monster happens. Through a series of events he ends up killing [someone], and in that moment he becomes a monster. He can never go back. He can never join society. He’s become corrupted by Henry and Polidori, been corrupted because of so many of the circumstances that surround him. It’s such an important part of Mary Shelley’s story, and seeing that happen through the eyes of the creature, experiencing it from his point of view, that was vital.”

By shifting the focus as he does, this allows Fessenden to play a little more with the Dr. Frankenstein character, in this instance Henry, with a bit more playfully complicated ingenuity than is typically the case with most adaptations of Shelley’s source material. “I feel that you slowly see that Henry is somewhat unhinged and incapable of providing a nurturing environment,” proclaims the filmmaker. “He’s filled with his own anger. Even in the ping-pong game, you see him snap and [Adam] gets an understanding of aggression and what that looks like. This slowly creeps into his consciousness.

“Maybe this will be too subtle for some tastes. But this was always my idea. I wanted to show the little tiny psychological shocks that shape us and make us feel damaged and confused. I wanted to show why it’s often so hard to come out okay. By telling the story through the creature’s eyes I could then play with Henry’s motivations and character a bit more creatively than I could have had I structured things from his point of view. Henry is the father figure here, and sometimes the lesson we learn from our father figures isn’t always a good one.”

These subtly shifting cracks in the human condition, these small emotional fissures that send people down complex paths where wrong looks right and attempting to do good can inadvertently lead to a more insidiously poisonous evil, these have been constants throughout Fessenden’s entire career. From Habit to Wendigo to The Last Winter to even his prior feature, 2013’s misbegotten giant man-eating fish creature feature Beneath, these thoughts have always been something the writer/director has consistently marinated upon. “I love that word,” he says with a touch of a mischievous whimsy. “Marinate. And I agree. These are themes that interest me.

“I love these great old stories. I’m sitting in my little home office and I’m looking at pictures of Frankenstein and Wolfman and the Creature. I love these aesthetically, these creatures that sort of represent something. But it is what is underneath that I find so fascinating. They’re all stories about our damaged nature and the psychological problems that we bring to our lives. If you see that as scary, then you understand them. These creatures are us.

“I always say I make sad horror movies. I’m sort of aware of the melancholy of life: what’s precious, what is fleeting and how susceptible we are to corruption and despair. All those things.”

As we sit and chat I’m reminded about the flood of emotions I had while reading Mallory O’Meara’s superb The Lady from the Black Lagoon and how much of what Fessenden is talking about mirrors many of the themes that are explored in the author’s biography of Milicent Patrick. She was the celebrated original designer of The Creature, the humanoid sea monster who lusts after Creature of the Black Lagoon actress Julie Adams. But her mark on history was erased, Universal’s makeup department head Bud Westmore taking credit for Milicent’s designs while making sure she never worked as an artist for a Hollywood studio ever again.

“It’s such a fascinating story,” says Fessenden. “Thank goodness for the book because it’s such a cherished story for those of us who love horror, that The Creature was designed by a woman. But also it’s such a sad story of the patriarchy just being everything that people hate about it. That Bud Westmore couldn’t handle the fact that he had this wonderful and talented woman working for him. He could have spun this story and said, ‘I mentored this woman.’ But instead he had to crush her. It’s really perplexing how people in power are so depraved, if I could use the word.”

Which brings the conversation back to the filmmaker’s movie. Henry and Polidori are the people in power. Not only do they end up working to crush Adam from living up to his potential, they also end up at one another’s throats, each trying to show superiority over the other. “The crush Adam,” explains Fessenden, “and in the process bring about all of the horror to come via their actions. But it’s more than that. Clearly, Polidori can’t stand that Henry’s smart enough to have made this monster, and so he wants to constantly remind Henry that he should get some of the credit.

“I think I’m just interested in damaged psychologies that lead to terrible things. Like in Habit, it’s the fact that the guy is obviously grieving and he can’t seem to put his finger on why, so he starts insisting that this woman is a vampire to all his friends. They just walk away because they can’t deal with somebody being that vulnerable. With Wendigo, no one wants to listen to the kid. They refuse to believe he knows what he’s talking about. That he’s afraid for valid reasons.

“And maybe that’s what this movie is about, too. I don’t make extreme movies. This isn’t A Boy’s Life, where you have the father bullying the kid and you go, that father’s bullying the kid and it’s despicable. It’s much more subtle than that, because I think that’s where you see that these shocks are still happening, where you’re forced to look at them even in a much more so-called normal world. The world’s despicability is often very subtle.”

All of which has oftentimes placed Fessenden ahead of the societal curve. No Telling and Habit are insightful looks at masculine insecurity and rage, both films made decades before the term ‘toxic masculinity’ entered the everyday lexicon. The Last Winter is an examination of the effects of climate change upon the world but features a collection of characters working for an oil company who, even though many of them are scientists, refuse to believe the scientific facts in front of them until it’s much too late. “I always used to joke that I make feminist films,” laughs the filmmaker. “But what does that mean coming from an old white guy? I’m not sure it means anything.

“But I have always seen the plight of animals and Nature and these unappreciated, deeply-overlooked structural elements in society that are taken for granted by the patriarchy, all of which I feel suffers from their taking everything for granted and destroying the world. It creates rage. It creates horror.

“I’m not blind. I’m a white guy and by and large I’ve lived a privileged life. But I have a sensitivity for whatever reason to these injustices and that’s really what my films are about. I like the marginalized people.

“This is why I love Get Out, because I always wanted to make a horror movie about what it feels like to be Black. What would it feel like at all times to feel that you have a target on your back in this society? And it’s only gotten worse since Trumpy Trump. So much worse. But as an old white guy I also knew I wasn’t the one to tell that story. So I love what [Jordan Peele] did with that movie. It’s incredible.”

Fessenden pauses for a moment as if in deep thought before he continues. “I really feel that’s always been my mission,” he states elegiac authority. “I want to please people, sure, but I also what to say to them, wake up! Look under the surface. Look how aggressive and violent our society is. It’s just so anti-life, it lacks tenderness and nuance. We literally have to talk about things like this with monster stories because it’s too delicate a topic.

“That’s my thing with identity politics. We should have that conversation, but it shouldn’t just be about standing up for your little tribe. It’s for what is decent, and if it is about being decent then you can lift all people together, including the knuckle-draggers who support this jackass in the White House. You can bring them along, too, if they are willing to rise to the occasion and be decent.”

– Interview reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle