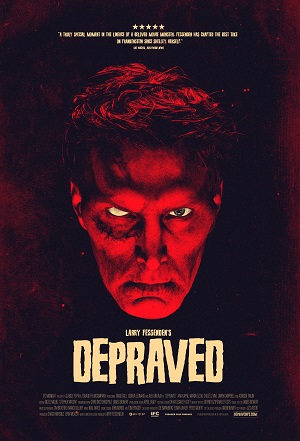

Fessenden’s Depraved an Emotionally Tragic 21st Century Frankenstein

Adam (Alex Breaux) is awake. He has no memory of who he is. No idea of what he once was. All he knows is that Henry (David Call) is his friend. The doctor and former Army medic takes care of him. He teaches Adam how to eat, how to walk, how to dress and how to talk. He schools him in literature and math. Henry even teaches him how to play ping pong, a game he begins to love even though he’s initially not very good at it. For Adam, all of this is good. It feels right. Residing in a secluded industrial neighborhood of New York in a sprawling loft apartment, for this inquisitive young man it’s hard to imagine life could get any better.

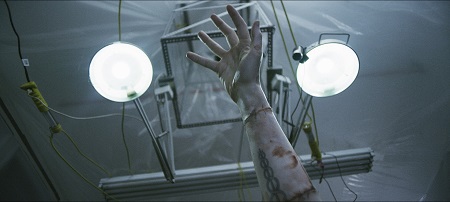

But not all is as it seems. Adam has jagged, grotesque scars all over his body, almost as if he were pieced back together body part by body part after some horrific dismemberment, Henry strangely cryptic when the pair talk about anything relating to his friend’s physical appearance. Additionally, there is the doctor’s acquaintance and financial benefactor Polidori (Joshua Leonard). He’s peculiarly ecstatic where it comes to Adam, the hyperactive, effusively self-indulgent and wealthy businessman acting like he’s Henry’s boss while also treating his patient as if he were his personal property and not a flesh and blood human being.

A heartfelt, deftly mature 21st-century reimagining of author Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, indie auteur Larry Fessenden’s Depraved is a movingly emotional monster movie that packs a pretty mean punch. It is a return to form for the Habit, Wendigo and The Last Winter filmmaker, the film reveling in the internalized minutia of its main character’s free-flowing psychological state as Adam comes to realize who and what he is. His evolving father-son relationship with Henry gives way to an understanding that the scientist and doctor doesn’t necessarily have his patient’s best interests at heart. This makes the vile insensitive narcissism displayed by Polidori all the more reprehensible, his toying with this creature’s blossoming emotions a key factor in the terrible carnage that will affect all three men by the time their collective stories reach their tragic conclusions.

Fessenden’s affinity for Shelley’s source material is obvious. There’s this great little opening prologue that initially seems inconsequential, a pair of fresh-faced young adults having a late-night conversation about their romantic future, their mumbling banter having a vulnerably silly eloquence that’s oddly charming. But as Adam begins to come into his own it quickly becomes apparent this interplay between two side characters, one of whom is never seen (in the flesh, at least) again, is far more essential than it first appeared it was going to be. Henry’s creature is haunted by a loss he can’t put words to in order to describe, and even as he learns what it means to have relationships and what it is to make new friends, there’s still a hole sitting at the center of his soul that he begins to suspect can never be healed.

This makes Adam’s journey towards becoming a being capable of unimaginable destruction so much more bleakly gut-wrenching than it otherwise would have been. It also makes him more of a fully-formed human than either of the other two men in his life prove to be. Henry and Polidori, no matter what their individual goals might be, are the true monsters. While each appears to be working towards the greater good, in the end it is their own self-aggrandizement that motivates their actions. Even the battlefield PTSD Henry suffers from due to not being able to save all of the wounded soldiers who fell under his care pales when compared to his egotistical brio as he self-assesses his medical and scientific abilities. Worse, while he treats Adam as a son, showering him with affection while urging on his physical and mental growth, the doctor is just as willing to liquidate his creation if his existence might at some point become troublesome.

I think one of the more interesting aspects of the film is that, during Adam’s trips into the public eye, while many do look at him and his numerous scars a bit sideways, most don’t treat him as a freak or as someone to be feared. If anything, many of the people he encounters go out of their way to be nice to him, trying to get a greater understanding of his situation as they attempt to get a better understanding of what might be going on with him. It is the influence of Henry and especially Polidori that leads Adam to inadvertently do the unthinkable, and it is when he accidentally treats kindness and empathy with inadvertent violence and bloodshed that the foundation for the climactic carnage is unintentionally poured.

Like almost all of Fessenden’s works, even the unctuously forgettable man-eating fish thriller Beneath, this one puts a greater emphasis on character and emotion than it does on cheap thrills or eye-popping visuals. This does not mean the director still can’t stage a stunning set piece or offer up a few dizzyingly hypnotic sequences (just watch pretty much all of Wendigo or the frigid last third of The Last Winter for proof of that). For this film the director works with his pair of cinematographers James Siewert and Chris Skotchdopole to a achieve a clinical, documentary-like approach that fits things nicely only for the story to become claustrophobically ephemeral during the film’s stormy climactic act. This makes for a suitably unnerving transformation that both mirrors Adam’s interior mental journey while it also pays deft homage to Shelley’s original novel, Fessenden finally diving head-first into the inherent terror of the tale with a brutal ferocity that’s close to incredible.

Not everything works, and other than a beguilingly quirky (albeit brief) performance by magnetic young actress Addison Timlin (whose character I will not talk about as to not spoil the surprise) most of the female characters are given frustratingly short shrift. But overall Fessenden has composed a mesmerizing little riff on the Frankenstein myth, and over 200 years after its first publication Depraved makes it clear there’s still plenty of electrifying life in Shelley’s classic tale, life audiences will likely keep thrilling to for untold generations to come.

Film Rating: 3 (out of 4)

Additional Link: