Gritty Joker an Overtly Theatrical Piece of Clownish Performance Art

There’s a lot to admire, maybe even love about what director and co-writer Todd Phillips (The Hangover, War Dogs) has done with his latest dark drama Joker. Not so much a revisionist take on the classic DC Comic supervillain as it is a reasoned, down-to-earth inspection of societal elements that could inadvertently create an all-too-human monster, the movie attempts to be a gritty look at wealth inequity, the shrinking middle class and the marginalization of mental health resources, especially in large urban multicultural metropolises. But even though his aspirations are high, and while technical elements for one of the director’s productions have never been better, I just didn’t find Phillips and co-writer Scott Silver’s (The Finest Hours) script to be complex or intelligent enough to get the job done. I don’t think it works, and for all the film’s many strengths I didn’t feel there were enough of them to make sitting through all 121 minutes of it worthwhile.

Gotham is in a state of unrest. There’s a garbage strike, the populace is angry and giant “super rats” wander around the back alleys and sewers. Billionaire businessman Thomas Wayne (Brett Cullen) is pondering a run for mayor on a platform of cleaning up the city and putting an end to corruption. While his mother Penny (Frances Conroy), a former employee of Wayne Enterprises, claims the political neophyte is a “good man,” frequently writing him personal letters and waits patiently for a response, Arthur Fleck (Joaquin Phoenix) isn’t so sure. A low rent clown with aspirations of becoming a standup comic, he’s given up on believing politicians can fix society’s ills or that the wealthy elite care anything at all for the working poor that make up the majority of Gotham’s populace.

There’s not a lot more as far as plot is concerned. What Phillips and Silver have constructed is an observational character study of a sad, lonely man who is growing increasingly angry thanks to the lack of understanding, opportunity, kindness and love he feels he deserves. There is something of an examination of mental illness and the lack of governmental care, and there are additional elements regarding the lingering scars of emotional and psychological abuse on the parts of parents towards their children. Some of this is highly effective, most notably scenes where Arthur learns about the dissolution of Gotham’s social services safety net and the canceling of his psychiatric treatment and access to medication. Other aspects most decidedly are not, including revelations regarding Penny and her connection to Thomas Wayne.

What does all this mean as far as Arthur’s evolution into the villain Joker is concerned? It’s a step-by-step process, one rooted in 1970s, early ‘80s New York cinema, most notably (and most obviously) the films of Martin Scorsese and Sidney Lumet. But while Phillips goes out of his way to channel the visual aesthetics of works like Dog Day Afternoon, Network, Taxi Driver, After Hours and The King of Comedy, his ends up being only a surface level dissection of these types of characters and this sort milieu. He doesn’t dig into what makes Arthur tick or find a way to scrutinize the roots of the societal and cultural ills that are helping to transform him into a cold-blooded killer. It’s all half-baked platitudes and patriarchal stereotypes, some of which feel so tone-deaf they border on being insulting.

But not always so. There are layers of truth that are admittedly affecting, and I appreciate that Phillips and Silver do make a valiant attempt to analyze the state of mental health treatment and care in the United States at this moment in time. Make no mistake, even if the movie exists in an unstated early 1980s major city Americana, it’s the here and now that the filmmakers are most interested in dissecting. What happens to Arthur is an injustice, at least early on, mainly because he is reaching out for help, going to counseling and taking his prescribed medication. When that goes away without any warning, with no chance to make other arrangements, that is a heinous thing that the wannabe comedian has every right to be angry about. It also just happens to be one of the only key plot elements that is studied with any sort of evenhanded introspective specificity.

Other than that, though, I’m not sold on the various plot mechanics Phillips and Silver have engineered for their dark antihero to become a brutal clown prince of crime. While I do not have an issue with the level of violence (it’s honestly nowhere near as indulgent or as repugnant as it easily could have been), the context in which it is often utilized is far too glib to resonate. Arthur’s masculine insecurities are tinkered and toyed with in ways that are more superficial than they are substantive. The girl he likes plants him squarely in the proverbial friendzone. He becomes the butt of the joke to a citywide Gotham audience when a disastrous video of his first attempt at standup is broadcast on a late night talk show host’s popular television program. He has to pay for a broken storefront sign out of his own pocket after he’s beaten up and left in an alley in a fetal position by a bunch of kids. It’s a lot of boo-hoo-hoo and oh-woe-is-me and precious little else, all of it content to revel in immature platitudes with no intention whatsoever to try and go above and beyond any of them.

I can’t say I was taken with Phoenix’s full-throttle, overtly theatrical performance. While he certainly gives all of himself, I just didn’t buy anything it was he was doing. Look at that weight loss! Look at the strange ways he contorts his body! Look at how many cigarettes he smokes! Look how his aggressive outbursts come out of places of austere stillness! Look! Look! Look! LOOK! Phillips gives him so much freedom it’s almost as if Phoenix is just making up everything he’s doing as he goes along without any directorial instruction or control. This isn’t so much a creation of a fully-formed three-dimensional character as it is an energetically flamboyant piece of performance art, hardly a positive as far as I was concerned.

The supporting cast is fine if underutilized, especially Robert De Niro as Arthur’s comedy idol talk show host Murray Franklin, the Academy Award-winning actor basically taking the Jerry Lewis role from The King of Comedy and making as much out of it as the script allows him to. But Conroy is left out to dry in a rather thankless role, while the magnetic Zazie Beetz is wasted as Arthur’s neighbor, single mother and object of affection Sophie Dumond. Granted, that she ends up being a male fantasy is somewhat the point, her involvement in the story a key ingredient in Arthur’s growing psychosis. But Phillips can’t seem to find a way to do anything interesting or intellectually stimulating with that idea, the actress left to fend for herself as she tries to figure out how her character fits inside all of this psychological chaos.

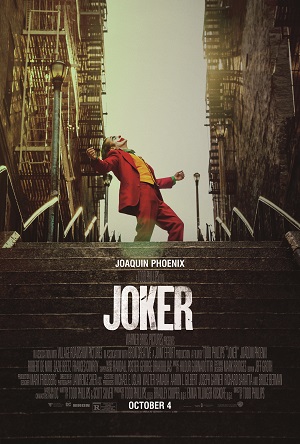

Still, the moments that do work are spellbinding. A sequence where Arthur in full Joker glory descends a massive staircase leading to his apartment building is glorious, while a scene a few beats before that at the gates to Wayne manor is humorous, chilling and heartbreaking all at once. Phillips is also aided in his pursuit to set a suitably ominous and discombobulating tone by composer Hildur Guðnadóttir’s (Mary Magdalene) stupendous, Oscar-worthy score, while Lawrence Sher’s (Godzilla: King of the Monsters) stunning cinematography gives the film a grungy, lived-in quality that’s nothing less than perfect.

As great as all of this is, none of these attributes makes me want to rethink any of what I have written. I didn’t like the movie, and I can’t be more definitive than that. As strong as many individual pieces and elements might be, none of them come together in a satisfying way. While I do think Phillips has something to say and that it does make some modicum of sense for him to utilize DC Comic’s most famous villain to help him state it, I find that I do not think he makes these statements with memorable, thought-provoking clarity. Joker wasn’t for me, and even if I were to dance with the devil in the pale moonlight and have a sudden desire to watch the world burn that still doesn’t mean I see my opinion changing anytime soon.

– Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 1½ (out of 4)