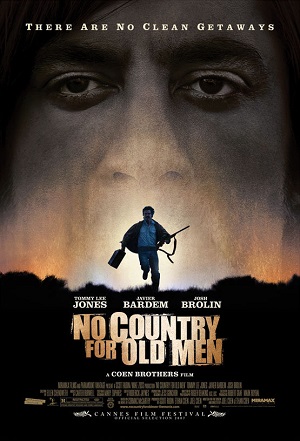

No Country for Old Men (2007)

by Sara Michelle Fetters - November 9th, 2007 - Four-Star Corner Movie Reviews

Coen’s No Country a Haunting Adult Western Thriller

Potent, powerful, compelling, elegant, unnerving and emotionally turbulent, Joel and Ethan Coen’s adaptation of Cormac McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men is a bona fide miracle. The best film the brothers have made since 1996’s Oscar-winning Fargo, this disturbingly eloquent thriller provides so much food for thought I’ll be contemplating it for months, maybe even years. Of all the pictures I’ve seen in 2007 maybe only two, the musical drama Once and the procedural mystery Zodiac, could be considered its equal, and someday this monumental achievement just might be regarded as the finest of the sibling filmmakers’ entire spectacular career.

Out in the middle of the deserted nowhere, Vietnam veteran Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin) has made a discovery. Amidst the chaos of bullet-riddled bodies and demolished off-road vehicles, he discovers a stash of heroin and a suitcase filled with $2-million in cash. Knowing it’s a bad idea, he takes the money back home to the trailer park, imploring his sweetheart Carla Jean Moss (Kelly Macdonald) too not ask too many questions.

Unbeknownst to Llewelyn, an assassin with a love for the kill by the name of Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem) is hot on his trail. This man lives by his own code of ethics that are so unhinged and bizarre even others in his peculiar profession, men like the folksy Carson Wells (Woody Harrelson), don’t have the first clue how to relate to him. That goes double for down-home Texas sheriff Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones). He is starting to feel like this changing world is finally getting the better of him. But Bell keeps doggedly investigating, hoping he’ll be able to at least warm the beguiling Carla Jean of the unholy terror silently stalking her beau before it is horrifically too late.

There is not a false beat anywhere inside this majestically devastating drama. From the first image of a shaggy-haired Chigurh being arrested in the middle of roadside nowhere, I could instantly tell this movie was going to be special. The Coens craft a wickedly devilish spell, cinematographer Roger Deakins (who, with this, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford and In the Valley of Elah is having an incredible year) setting the tonal thermometer for the entire tale in those opening few seconds.

Some will have problems with the picture, mostly with the abruptness of its ending. The filmmakers pull off a Psycho-like twist at the most impromptu of moments, and what viewers thought was the dramatic point of their story turns out to be only a catalyst driving another character’s stark realizations. It is here that the bigger picture is cleverly revealed, the inescapable meditatively corruptive horrors the Coens are outlining only growing in majesty from this point forward.

I don’t know to describe Bardem and what it is he is doing as Chigurh. This is a titanic portrait of evil right up there with Anthony Hopkins in The Silence of the Lambs or Robert Mitchum in The Night of the Hunter. He is eerily unforgettable, the performance seeping under my skin like a terrifying nightmare and each time he appeared my heart stopped, my breath ran cold and I shuddered at the thought of what he might do next.

Nearly his equal are both Jones and Brolin. While that is not a surprise for the Oscar-winning veteran, for the latter actor watching him blossom in 2007 has been a magnificent joy. Between the Robert Rodriguez section of Grindhouse, the aforementioned In the Valley of Elah and Ridley Scott’s American Gangster the actor has cemented himself as singularly gifted talent with astonishing range and acres of untapped potential. Brolin digs right into Moss, not afraid to bring out all sides of his complex persona no matter how dark or dangerous those pieces might appear to be. He’s both hero and antihero, sinner and saint, and watching his journey is as pulse-pounding as any I’ve seen this year.

There is more I could say, not the least of which is the Coens’ refusal to allow audiences a moment of reprieve for a bit of cathartic release. For them, the way this world works there is no place for such emotion, no time for redemptive tears when times change and people of every generation are faced with the confounding perplexities of the present. Indeed, within the framework of this film it truly is No Country for Old Men, and as that harsh realization presents itself the only emotion left is a form of quietly overpowering grief.

Film Rating: 4 (out of 4)