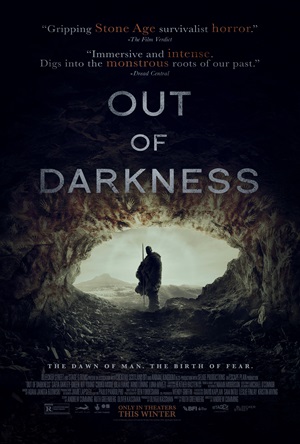

Out of Darkness Journeys to the Prehistoric Past to Analyze Humanity’s Uncertain Future

Six weary travelers wash up on a distant, unexplored shore: Adem, the group’s leader (Chuku Modu); his pregnant wife Avé (Iola Evans); their inquisitive son Heron (Luna Mwezi); his brother Geirr (Kit Young); wise elder Odal (Arno Lüning); and teenager Beyah (Safia Oakley-Green), a “stray” they picked up before setting out on their journey. They have precious little other than a few weapons and their ragged clothes. Their provisions were almost entirely lost at sea.

But they still have hope. They have come to this strange, barren land to start fresh, and Adem is certain he has done the right thing by leading them here. He believes they will find shelter and there will be game for them to hunt. They will claim these shores for their own, and nothing will stand in their way.

Set roughly 45,000 years ago, Out of Darkness is hardly the first dramatic thriller to focus on prehistoric humanity. From One Million B.C. to Quest for Fire, there have been plenty of attempts to visualize what life may have been like during this period. Some of these stories are gloriously fantastical, featuring stop-motion visual effects overflowing in giant creatures, death-defying escapes, and monosyllabic clans pummeling one another into submission. Others are more grounded, attempting something akin to cinematic time travel in their zeal to showcase how it may have actually been for the first humans.

Making his feature-length debut, writer-director Andrew Cumming and his co-writers Ruth Greenberg and Oliver Kassman straddle the fence between these two storytelling styles. This film is lived-in and grounded, showcasing a dirty, disheveled landscape similar to the aforementioned 1981 Jean-Jacques Annaud classic Quest for Fire or 2022’s violently histrionic battle royale The Northman, directed by Robert Eggers. But it also has no qualms dipping into gory creature-feature histrionics, reveling in nasty bursts of violent bloodletting that wouldn’t have been out of place in any of a dozen 1980s schlock favorites, like Conquest, The Sword and the Sorcerer, or The Warrior and the Sorceress.

Not that the filmmaker is out to craft a B-grade genre piece with nothing more on its mind than the crassly sensationalistic. Even with the cracked skulls, dismembered jaws, and gruesome impalements, this isn’t simple Stone Age exploitation. Far from it. Cumming is telling a story of human misunderstanding that’s as sadly true today as ever in this realm of mystery, wonder, and fear. The most dangerous creatures lurking in the wilderness may be Adem and his followers, not the monstrous entity they’re stalking, and it is this revelation that will determine whether or not any of them survive to plant the seeds of the brave new world they hope to create.

The idea is that Adem is possibly leading them all to ruination after Heron is mysteriously stolen from the group by an unknown assailant. They all have their own ideas of what took the boy, ranging from the logically grounded to the hysterically fantastical. But he is their leader, and so they do what is asked of them with little hesitation. This includes heading into a thick forest that their adversary may call home and where day quickly becomes night and finding a safe way out is next to impossible.

But while they follow Adem, they do not do so blindly. As things become increasingly dire, each starts to question whether or not they’re doing the right thing. Some want to make a sacrifice to the demons they believe rule the area. Others think the beast they’re tracking isn’t supernatural at all, and the only mistake Adem is making is to try and hunt it in its own territory and not in a spot of this small group’s choosing instead.

As the outsider looking for a home, Beyah quickly becomes the focal point of this drama. She knows she will be the one sacrificed or left behind if Adem decides (or any of the others, if they can bend his will to theirs) this is the best course of action. She also understands he must wait to make this determination, because, if his son does die or if anything tragic happens to Avé, she is the only fertile female left to procreate with.

This gives Cumming plenty of material to play with and ponder, and for most of his film’s briskly paced 87 minutes, he does this with surprisingly multifaceted balance. He allows Beyah to come to the forefront with confident grace, and even as he keeps everyone running from one nasty encounter to the next, the director refuses to rush the character development.

The technical facets are exemplary. Cinematographer Ben Fordesman (Saint Maude) creates a visual aesthetic dripping in primordially unhinged restlessness. Editor Paulo Pandolpho allows scenes to play out with an inherently distressing and distinctly sinister rhythm. I may have liked the cacophonously belligerent score courtesy of composer Adam Janota Bzowski (The Marsh King’s Daughter) most of all, which has a spine-tingling otherworldliness I was instantly drawn to.

There are moments where things get uncomfortably didactic, and the climactic twists Cumming whips out with jarring abandon did not catch me off-guard. But just because these revelations are obvious does not mean they are ineffective. What the filmmaker is saying about the people inhabiting this prehistoric world has more to do with what is going on right this second than it does anything else. Out of the Darkness shines a light on modern troubles, and by dipping into the past, the film asks the audience to consider how tenuous and uncertain humanity’s future survival truly is.

– Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 3 (out of 4)