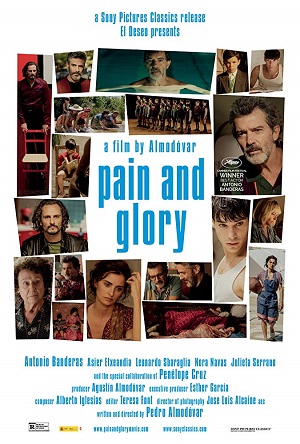

Pain and Glory (2019)

by Sara Michelle Fetters - November 8th, 2019 - Four-Star Corner Movie Reviews

The Vagaries of Life à la Almodóvar in Masterful Pain and Glory

For over four decades Spanish director Pedro Almodóvar has pushed the cinematic envelope. He has done so inside the confines of character-driven stories and without the aid of technological advances in visual effects or by utilizing hyper-modern editing techniques. He has crafted a bevy of memorable thrillers, comedies and kitchen sink melodramas, most of which are a combination of all of the aforementioned genres stirred together into one glorious mélange. He is one of the great auteurs of our time, and with a filmography that speaks for itself I don’t feel like this is a statement those familiar with his work are going to disagree with.

His latest drama Pain and Glory is one of Almodóvar’s most personal storytelling endeavors. It is also one of his best, which is saying something considering this is the guy that made Labyrinth of Passion, Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, All About My Mother, Talk to Her and Volver. The film also forms a masterful, mesmerizingly inventive trilogy with two other of the director’s most notable motion pictures, 1987’s Law of Desire and 2004’s Bad Education. But where those two were sly meditations on the filmmaking process that ventured into hyper-sexualized terrain heavily influenced by the likes of film noir and satirical slapstick comedy, this one is more down to earth in its melancholic fervor.

Celebrated filmmaker Salvador Mallo (Antonio Banderas) does not believe he will work again. A variety of health issues, most relating to his ailing back, have left him in constant pain, and because of that he’s taken to self-medicating while also becoming something of a reclusive, borderline agoraphobic, hermit. But the anniversary of his first major international success has brought him partially out of his shell, the director even reaching out to that picture’s star Alberto Crespo (Asier Etxeandia) for this first time in three decades to join him for a retrospective post-screening Q&A. Mallo was upset that Crespo did not play the part the way he wanted him to, and because of this he’s never given the actor credit for delivering a performance that people have loved for 30 years.

As simple as this story is, this isn’t the only one Almodóvar is telling. There is the medical drama. There is the sight of Mallo trying heroin for the first time to help alleviate the pain in his back. There is the back-and-forth brotherly antagonism that develops between him and Crespo as they begin to realize they aren’t as different as they’ve allowed themselves to believe for over half their lives. There is the brief reunion between Mallo and a former lover from his past who helped fuel his creative fire, intensified his romantic passions and broke his heart due to their constant battle with addiction.

Most of all, there is the director looking backwards to his youth as a young boy (Asier Flores) and his relationship with his beloved, wearily determined mother Jacinta (Penélope Cruz). It was here his desire to tell stories was born. It was here his imagination was inflamed by the likes of handyman Eduardo (César Vicente) whom he would teach to read and write. These recollections come crashing back like waves against the seashore, Mallo overwhelmed by their emotional weight and significance. Even though he believes he’ll never make another motion picture, the artist still feels compelled to put pen to paper and write all of these recollections down before they disappear into the ether of his memory forever.

It’s a lot, yet Almodóvar organizes it all with magnetic precision. There’s a spellbinding sequence where Crespo comes across an old monologue amongst Mallo’s writings entitled “Addiction” and immediately concludes he is the actor to give these words to life. The pair squabble over the piece, but when they do sit down to finally decide if the actor will get the filmmaker’s permission to perform it Almodóvar treats this intimate conversation like a balletic dance of acrobatic intellects. Even though their minds have been dulled by time and abuse both are reinvigorated with youthful intensity at the thought of what might be accomplished if they can come to a mutual understanding. It’s an electrifying sequence, the quiet intensity leaving me in a state of breathless awe.

But this is only one moment in a film overflowing in them. Almodóvar’s specificity of vision is stunning. The sequences set in the past with Cruz and newcomer Flores are full of surprises, while later scenes featuring Jacinta in her 80s (now portrayed by the great Julieta Serrano) are maybe even more so. Then there is that reunion with Mallo and that former lover. It left me speechless, the clarity of what was being said even though both individuals in the scene hardly knew what to say one another extraordinary.

At the center of it all is Banderas. This is arguably the best performance of the actor’s storied career, at least since the last time he worked with Almodóvar in 2011’s The Skin I Live, probably since the pair’s most controversial project 1989’s Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!, an NC-17 stunner that’s only grown in significance since its debut. There is a lucidity to what Banderas is doing as Mallo that is enthralling. The actor’s physicality, how he subtly contorts his body as he reacts to all that is happening, it’s all incredible. Banderas conveys so much often by doing very little, and even in scenes where he’s almost a secondary character, like in interviews with his back doctor or while sitting in his mother’s bedroom as she tells him in detail how she wants him to handle her burial arrangements, the full weight of his emotional elasticity still explodes in a number of imaginative ways that often left me shell-shocked.

But none of that compares to what Almodóvar saves for the climax. The last scenes of his movie are priceless, the poetic magnificence of this conclusion hitting me fast and hard, the floodgates opening and suddenly I was a waterfall of tears as I euphorically drank it all in. This is the director at his best. He might not push the technical boundaries of the cinematic medium but that does not mean he still isn’t an iconoclastic risktaker testing the limitations of what melodrama can be.

Almodóvar gives the creative process over to the viewer, believes in their imagination and lets his audience fill in the narrative spaces he purposefully leaves blank for them to take ownership of. Memory of who we were coupled with who we wanted to be is augmented by the realization of who we really are in the present can hurt in some profoundly internalized ways, yet at the same time so does refusing to look back at our lives so we can understand ourselves, and by extension others, more fully. There is jubilation and wonder to be found in these remembrances, moments of pure bliss that are beyond imagining. This is what Almodóvar has delivered with Pain and Glory, this introspective marvel a storytelling masterclass viewers all over the world should make it a priority to see.

– Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 4 (out of 4)