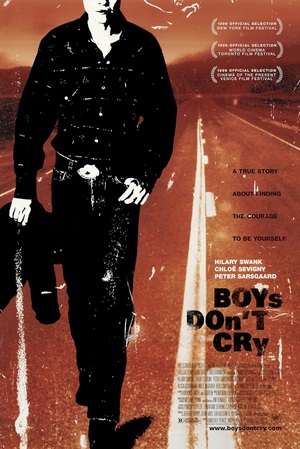

Unforgettables: Cinematic Milestones #34 – Boys Don’t Cry (1999)

by Sara Michelle Fetters - November 29th, 2024 - Features

Celebrating the complicated, problematic legacy of an essential entry in the LGBTQ cinematic canon on its 25th anniversary

NOTE: This feature originally appeared in the November 1, 2024 edition of the Seattle Gay News.

It’s not a stretch to say that director Kimberly Peirce’s 1999 Academy Award-winning debut Boys Don’t Cry helped save my life. I was in a horrible psychological place during the late 1990s: struggling to keep a job, barely paying bills, kicked out of the University of Washington for not attending class. While my roommate, family, and closest friends didn’t necessarily see it, I was inching toward the end of my rope. Suffice it to say, I was pretty good at keeping things like that hidden.

When I saw Peirce’s drama in October of that year, it was like a switch went off in my brain. The tragic story of Brandon Teena struck a nerve, and I knew I had to make changes right then and there. Within months, I had found a therapist and began coming out to my friends. I started going to support groups at Ingersoll Gender Center and made the acquaintance of the incredible Marsha Botzer. Soon after, I let my family know what was going on. By the middle of 2000, I was openly living and working as my authentic self. Best of all, I was happy.

What’s hard to explain is why this graphically violent, sometimes exploitative docudrama that took several liberties with Teena’s real story (which culminates in his rape and murder) spoke to me the way it did. Peirce’s ferocious direction certainly helped, as did Jim Denault’s searingly immersive cinematography. The top-notch ensemble was electrifying, led by relative newcomer Hilary Swank (hardly a household name, even if she’d appeared in the Buffy the Vampire Slayer movie and had the lead in The Next Karate Kid) and featuring the likes of Chloë Sevigny, Peter Sarsgaard, and Brendan Sexton III,

Yet it was how Peirce and co-writer Andy Bienen structured their narrative that impressed me the most. Much like the monumental 1990 documentary Paris Is Burning, there was a “Trans gaze” to the film that hit me like a sledgehammer. It was hardly subtle, and sometimes even sensationalistic, but nevertheless Peirce confidently and daringly forces the audience to see everything — hopes, desires, longings, joys, loves, and, yes, the bone-chilling terrors — from Teena’s perspective, making them part of his Trans narrative. This gaze was not always successful, and certainly not without uncomforting voyeuristic missteps, but it’s still there. For a relatively mainstream motion picture hitting theaters at the tail end of the 1990s, this was no small thing.

It’s doubtful that few viewers had experienced anything like Boys Don’t Cry unless they had wanted to do a deep, scene-by-scene analysis of Ed Woods’s much-maligned 1953 drama Glen or Glenda, were a big fan of underground provocateur Doris Wishman, or had the good fortune of catching Paris Is Burning during its theatrical run. I found it eye-opening. Moreover, it got me to see the lie I had been trying to erase every time I angrily peered into the mirror.

But Peirce’s film is also the definition of “problematic.” It has not aged gracefully. Not that this is surprising. Few motion pictures from decades past hold up in every way when placed underneath a modern microscope, especially ones that deal with topics like race, sexuality, and gender. What passed muster in 1999 at best looks quaint today, and at worst comes off as risibly offensive. Plus, Peirce and Bienen took significant liberties with Teena’s story. They left out essential characters (cutting out one of the murder victims entirely). This list of things that feel off and even downright wrong about Boys Don’t Cry only grows longer from there.

Partially this is due to Peirce and Bienen breaking down the story into its simplest, most straightforward elements. That they do this with skill and precision is laudable. That they inadvertently play into several Trans stereotypes that were common in 1999 but are considered shamefully egregious in 2024 sadly is not. Scenes where Teena stands in front of a mirror changing his reflection come across as if he is clandestinely putting on a costume instead of doing the work to be his authentic self. These moments were difficult to watch 25 years ago; they’re almost impossible to sit through now.

Then there is Swank’s performance. It’s magnificent, make no mistake about that. I have no issue with her winning the Oscar for portraying Teena. It’s bracingly introspective work, fueled by a nakedly raw vitality that’s haunting. I have her autograph that a friend snagged while attending the 2000 Independent Spirit Awards that I treasure. It means a lot to me, almost as if it is a personal signifier of the official start of my own transition.

However, for all of Swank’s dexterous skill, for a Trans viewer, there is something of a disconnect between the truth of dealing with gender dysphoria and her creating a rather glossy facsimile of it for viewers. While Peirce, much to their credit, did consider Trans actors for the role, it’s difficult now not to wonder how much the film would have changed had the casting gone in that direction. Going with Swank does feel like somewhat of a mistake.

Yet, for me, this effort remains essential, even with these challenging, maybe even angering, aspects. Context is key when watching it, and in many ways, it is the things that Peirce gets wrong that make the film a crucial entry in the LGBTQ cinema canon. I firmly believe that the only way to keep moving forward is to know where we have been, and knowing how we have told stories such as these in our past is vital in helping us to effectively tell similar ones in the future. One wonders if projects like I Saw the TV Glow, Emilia Pérez, Lingua Franca, A Fantastic Woman, Tangerine, Bit, any one of the genre-jumping offerings from 20-year-old Aussie wunderkind Alice Maio Mackay, and so many others would have seen the light of day had Peirce’s drama not been a critical and box office success.

All of that aside, it remains my personal connection to Peirce’s debut that keeps me coming back to it again and again and again. I’ve watched it six times in the theater. I’ve seen it at least another six or so at home. I thankfully do not know if I’d have committed suicide had I not watched Boys Don’t Cry when I did. I tend to think I wouldn’t have, but that I can’t truly say speaks volumes.

Celebrating its 25th anniversary, Boys Don’t Cry is available on DVD and Blu-ray, and can be purchased digitally on multiple platforms.