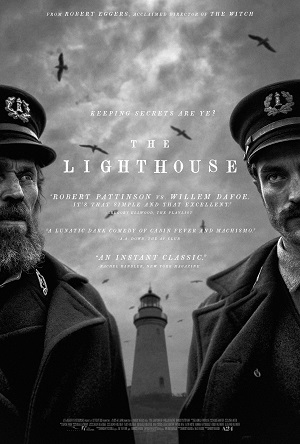

Eggers’ Lighthouse a Suspenseful Maritime Yarn of Isolation and Madness

On a secluded stony island located in the vast, stormy nowhere just off of the New England coastline, seaman Thomas Wake (Willem Dafoe) and Ephraim Winslow (Robert Pattinson) have set down to begin their four-week stint manning an all-important lighthouse. Each day Winslow gets up, lugs coal wheelbarrows full of coal, cleans the station and does whatever other menial tasks Wake has instructed him to do. The pair chat about their past lives, share their evening meals and try as best they can (and oftentimes failing) to not get on one another’s nerves. It’s a tedious month-long slog filled with backbreaking toil and unimaginable isolation even if the pay is good, both men looking forward to getting back to civilization as soon as the boat back to the mainland arrives with their relief.

Thanks to a cranky seagull, Winslow’s deteriorating sense of reality and a seemingly unending storm that has lengthened their stay far beyond normal, things don’t end up going particularly well for these two men in writer/director Robert Eggers’ latest psychological freak-out The Lighthouse. A follow-up to his unforgettable 2015 debut The Witch, the filmmaker again toys with his audience in ways that grow increasingly unnerving and unctuous as his story progresses towards conclusion. It’s like a Herman Melville story that’s been crossed with the writings of Anton Chekhov, Greek mythology and Roman Polanski’s Repulsion or The Tenant, all of it set in a desolate windswept wilderness where the only sanctuary is a creaky wooden homestead that feels like it could blow right off of its unsteady foundation at any given second. The film is a feast for senses even as it screws down harder and more debilitatingly upon the viewer’s sense of self, Wake and Winslow’s fragmenting emotional states of being transferred to the audience with insidiously unrelenting ferocity.

Gorgeously shot in black and white by cinematographer Jarin Blaschke (Down a Dark Hall) and featuring stunningly meticulous sound design that drowns the viewer in its uncomforting ambiance, Eggers is all about creating a discombobulating atmosphere where fantasy and reality cease to exist. This is an eerie dreamscape of tedium and chaos where one-eyed seagulls are harbingers of doom and visions of tentacled monsters are casually revealed in the piercing, all-seeing glow of the lighthouse as its beams are reflected off the impenetrable rain and fog assaulting the little island. All of this makes the film a visual and aural triumph, Craig Lathrop’s (Wolves) meticulously dilapidated production design deserving of special recognition for just how authentically weathered and ascetic it ends up proving to be.

At its heart, however, Eggers’ moody, esoteric descent into madness is a showcase for two gifted actors at the height of their powers. Pattinson once again shows he’s one of the best actors of his generation. His willingness to take risks, to stick himself out there in the most ridiculous of situations and treat them with such magnetic seriousness, this skillset works perfectly for him here. As for Dafoe, he’s a grizzled, flatulent hoot he spews as much truth as a lapsed Catholic sitting on a stool at the local bar drinking whiskey long after the Sunday service has concluded. He’s a foul-mouthed spigot of fire and brimstone only his religion comes more from a mixture of a bottle of booze and a lifetime on the sea than it does anything found in either the Old or New Testaments.

The two play off of one another magnificently, each poking deliberate holes in the other’s life stories that at first lead to playful bouts verbal tomfoolery only to later became lethal jousts of anger and accusation that could very well foreshadow the pair’s mutual doom. Eggers writes dialogue for the pair of them that sound directly lifted from Melville and other linguistic writings of this late 19th century period in New England history, both actors letting the director’s maritime, almost Shakespearean-like monologues drip off the tips of their respective tongues as if both had been speaking in that style from the moment they uttered their first spoken word.

What’s it all mean? Where is Eggers going with all of this? I honestly can’t tell you. The filmmaker is being purposefully vague as to what happens to Wake and Winslow, the line between what is physically going on during their stormy confinement and what is taking place entirely inside each man’s mind terrifyingly ambiguous. His film has a haunting atmosphere that is unbearably suspenseful. Yet at other moments things become quite humorous and amusing, only for Eggers to once again turn on a dime and let the inherent terror of the perilous situation the men find themselves hit home as if his motion picture was nothing less than a massive wave crashing into the ragged rocks of common sense and normalcy with unforgiving savagery. The Lighthouse is one of 2019’s most uniquely satisfying creative endeavors, and even if I’m still not sure what the point of it all is I just as assuredly cannot wait to head back to the theatre and weigh anchor on a second viewing as soon as possible.

Film Rating: 3½ (out of 4)