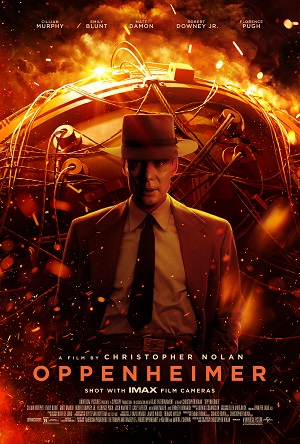

History, Ego, and Scientific Discovery Explode in Nolan’s Ambitious Oppenheimer

Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer is the type of old-school, star-studded, epic historical biography Hollywood does not make anymore. It’s shot on 70mm IMAX film. A full three hours in length. Overflowing in directorial flourishes reminiscent of Stanley Kubrick and David Lean. No penny pinched — every dollar is up on the screen. All of the technical aspects — from costumes to production design, set decoration to makeup, editing to cinematography, original score to sound design — border on perfection. Make no mistake, it is nothing short of extraordinary.

Yet the film, a time-bending chronicle of the birth of the atomic bomb and an examination of its complicated creator, American theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer (magnificently portrayed by veteran character actor Cillian Murphy), is as frustrating as it is fantastic. This is a sprawling, sometimes self-indulgent opus that determinedly keeps its central figure in the spotlight but often reduces many of its key supporting players to ephemeral one-dimensionality. Nolan has crafted something so exhilarating that its more maddening aspects can’t help but stick out like a sore thumb, and I’ll be curious to discover if my opinion of the finished product improves or diminishes on a second watch.

I am not a Manhattan Project historian. I only know what I learned about Oppenheimer, the Trinity Test, and his subsequent fall from grace from what we briefly covered in my AP American History class in high school. Even though Nolan’s dense, multilayered script is based on the Pulitzer Prize–winning American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, I can’t say I have the first clue how closely the director’s narrative hews to its source material.

If anything, Oppenheimer resembles Oliver Stone’s Academy Award–winning docudrama JFK more than anything else. This is also an ambitious retelling of historical events that shifts from color to black-and-white and back again as it moves backward and forward through time, as if linear storytelling was boringly passé. The film is slickly edited by Jennifer Lame (Tenet), stunningly shot by Hoyte Van Hoytema (Nebraska), and features a titanic score courtesy of composer Ludwig Göransson (Black Panther) that instantly ranks as one of the Oscar winner’s crowning achievements. These are all attributes Nolan’s film shares with Stone’s 1991 favorite.

But it shares other aspects as well. There is a layer of sensationalism that keeps much of the core emotional dynamics that rumbles throughout the piece irritatingly at arm’s length. The opening act, where Nolan introduces his central figures and starts placing his pieces on the chessboard, is messy, muddled, and strangely hurried. Many of the female characters are nonentities, and their plights rarely matter in a meaningful way. Sometimes, the cavalcade of superstar faces becomes a game of “look who that is!” instead of a shining moment for a talented performer to disappear into a role and make a lasting impression.

Does all of this make Oppenheimer something of a mixed bag? Certainly, but in some ways that’s more of a plus than a minus. Nolan is taking big swings and challenging the audience to pay attention. He keeps the viewer on their toes with sizzling dialogue reminiscent of 12 Angry Men or Seven Days in May and keeps the visual and audio razzle-dazzle to a surprising minimum. He presents Oppenheimer as a complex figure who is neither hero nor villain, never passing judgment on his accomplishments, thus allowing the audience to decide for themselves whether or not the seismic change he unleashed upon the world was an unpardonable sin or nothing more than a tragic inevitability that humanity was destined to discover with or without him.

What I imagine will not come as a shock to anyone is that the film’s midsection at the Los Alamos testing site in New Mexico is the film’s chief asset, in particular the actual Trinity test itself. Nolan is firing on all cylinders throughout this portion of the story. Every scene between Murphy and Matt Damon — portraying project lead General Leslie Groves — is pure poetry. The byplay between Oppenheimer and his determined team of scientists crackles with urgent pizazz, most notably any interaction he has with future hydrogen bomb enthusiast Edward Teller (Benny Safdie) or longtime friend and colleague Isidor Rabi (David Krumholtz).

It all builds to that Trinity test, and the whole sequence is nothing less than magnificent. Nolan channels some mystical combination of Terrence Malick, David Lynch, Kathryn Bigelow, and Michael Bay during the buildup to and aftermath of that fateful July 16, 1945, morning, so much so that it was almost as if sweat were dripping right off the screen. It’s magnetically tense, and by the time the bomb drops and the world as everyone knew it up to then changed forever, I’d moved so far up to the edge of my theater seat, it’s a wonder I didn’t fall off.

I’ll be curious to see how general audiences react to the final act of Nolan’s sprawling creation. Everything is presented within a two-piece framing device. One chronicles an inquest into Oppenheimer’s past associations and communist ties as they pertain to his security clearance. The other looks at the Senate congressional hearing for potential cabinet nominee Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.). They are utterly intertwined, and each section is chock-full of fascinating moments and startling revelations.

This is also where Nolan is his most unrestrained. Some of his flourishes work extremely well, like the casual nudity between characters sharing a postcoital conversation or a Machiavellian maestro reveling in the intricacies of a plan that’s been years in construction and that is hopefully about to pay dividends. But other aspects don’t work as well, and having characters who were mostly invisible throughout the first two-thirds of the story suddenly show up to make the most impactful revelations considerably mitigated my emotional connection to the material.

It should be noted that, as much as Florence Pugh and Emily Blunt try, the women in Oppenheimer’s life barely register. After a wonderful introduction, Pugh is subsequently underutilized to such a degree it’s infuriating. As for Blunt, who portrays Oppenheimer’s wife Katherine “Kitty” Puening, while history tells us she was a complicated woman with one heck of a backstory of her own, that’s only hinted at in the sparsest of brushstrokes here. Yet, thanks to one superb scene during the inquest where the actor magnetically spars with an aggressively pugnacious Jason Clarke, she manages to come out of this relatively unscathed.

I will see Oppenheimer again. Even though Nolan’s not staring into the impenetrable galactic heavens as he did in Interstellar, showcasing mystical illusions as in The Prestige, navigating the heroic retreat of Dunkirk, or introducing Batman’s arch enemy The Joker with action-packed gravitas, this is still every bit the cinematic magnum opus any of those motion pictures were. Whether or not it will leave a similar lasting impression, only time will tell.

– Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 3 (out of 4)