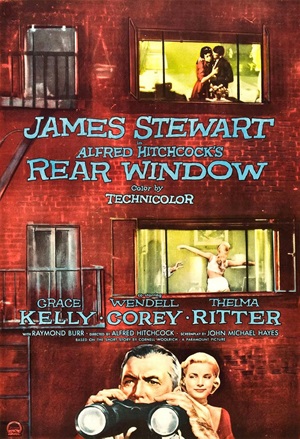

Unforgettables: Cinematic Milestones #33 – Rear Window (1954)

by Sara Michelle Fetters - October 30th, 2024 - Features

Rear Window – Alfred Hitchcock’s masterpiece of voyeuristic suspense and the preternatural beauty of Grace Kelly remain as timeless as ever

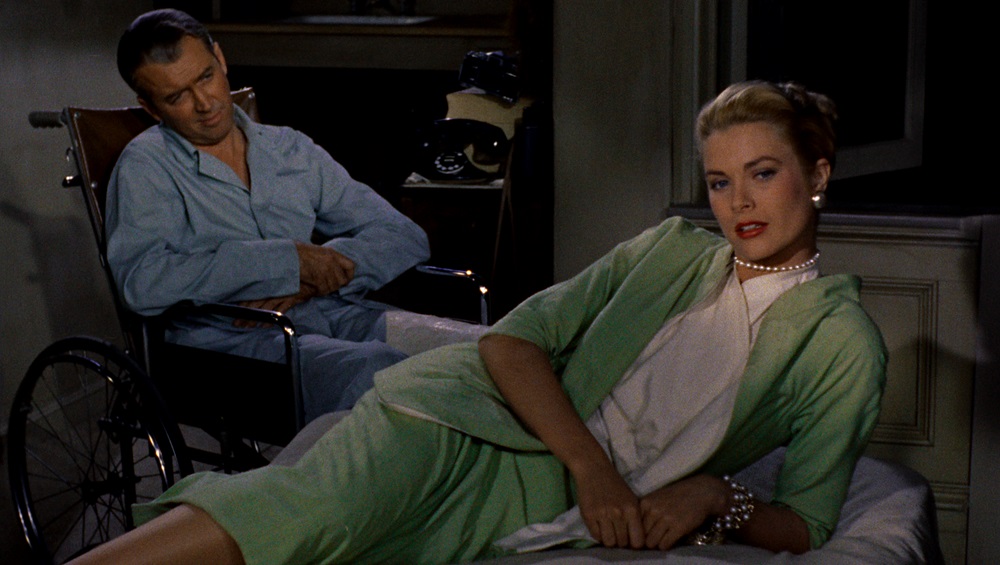

Grace Kelly’s first appearance in 1954’s Rear Window might be the greatest movie star entrance of all time. Granted, the list for this honor is a long one. I’d happily listen to anyone who wanted to fight for John Wayne (Stagecoach), Toshiro Mifune (Seven Samurai), Marilyn Monroe (Some Like It Hot), Sean Connery (Dr. No), Lauren Bacall (To Have and Have Not), Orson Welles (The Third Man), Gene Wilder (Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory), Arnold Schwarzenegger (The Terminator), John Travolta (Saturday Night Fever), Harrison Ford (Raiders of the Lost Ark), or Rita Hayworth (Gilda) — all of whom make my particular shortlist for this honor — but ultimately their arguments would fall on deaf ears.

No — for me, it’s Kelly by a mile. Hovering over an initially bewildered L.B. Jefferies (James Stewart) as he attempts to jolt himself back awake, her character — the elegantly dashing New York socialite Lisa Fremont — looks deep into the camera, her ruby red lips and piercing blue eyes taking over practically every inch of the frame. While everything else in the background is intentionally fuzzy, cinematographer Robert Burks makes sure nothing about Kelly’s preternatural beauty is even slightly out of focus. In this moment, Fremont is Jefferies’ entire world. More than that, she knows it too.

But like all such iconic entrances, this moment isn’t only about an actor making a purely physical impact on the proceedings. Alfred Hitchcock uses Fremont’s introduction to crystalize all of the themes and ideas his classic thriller will explore for the remainder of its 112-minute running time. Issues of class, social status, sexuality, communal responsibility, personal freedom, exploitation, and even boredom all come into play, and the brief conversation the pair have immediately after their kiss (one of the sexiest ever on film) succinctly foreshadows all that is to happen with subtly clever precision.

Considering its legendary status as one of Hitchcock’s crowning achievements (Vertigo is frequently listed as one of the best motion pictures ever made, but critical consensus typically puts this one not too far behind), I doubt I have to spend too much effort outlining the plot. Jefferies is an award-winning photojournalist who is homebound due to a broken leg. Dealing with extreme tedium, he starts spying on his neighbors through the window overlooking the common area in the middle of his Manhattan apartment complex. During this prurient exercise, Jefferies believes he has witnessed the before and after moments of salesman Lars Thorwald (Raymond Burr) murdering his bedridden wife. But as he has no proof and did not see the actual event, it’s an open question as to whether his suspicions are valid.

I came to Rear Window while in grade school. Our local Spokane PBS station programmed a month of Hitchcock double bills for late Saturday nights, and I got permission from my parents to stay up and watch them. The others I remember getting a look at include Psycho, The Birds, The Trouble with Harry, Shadow of a Doubt, and Rope, but, in my memory, this was the one that kicked off the series, and I was understandably mesmerized.

My fascination with Hitchcock’s playfully lithe and technically precise thriller has only grown over the years. I adore Thelma Ritter’s hilariously deadpan performance as Jefferies’ world-weary and streetwise nurse, Stella. I’m captivated by the spectacular production design and how Burks’ camera intimately captures every facet of it. As for Edith Head’s glorious gowns, they are as immaculately exquisite today as they were in 1954.

I love how Hitchcock makes the viewer complicit in Jefferies’ voyeuristic escapades. We see what he sees, as he sees it. More importantly, we feel what he feels (curiosity, excitement, terror, shame, etc.) in the exact moment as he does. I have no idea how Hitchcock and Stewart achieved this, let alone with such invisible virtuosity.

Then there is that famous ending. It shouldn’t work (Jefferies, trapped in his wheelchair, faces down Thorwald in his darkened apartment with only his camera’s flashbulbs as a weapon), and yet Hitchcock still makes this one of the most paralyzingly suspenseful set pieces of his directorial career (which is saying something). Burr, who up to now we’ve only seen from afar, manifests all of his character’s insecurities, cluelessness, and growing rage with striking authority. And Stewart’s terror builds with intensely focused authority. Few climaxes in all of film history work any better than this one.

Yet it is Kelly I will always think of first when it comes to Rear Window. She may have deservedly won her Oscar for The Country Girl (also released in 1954), but it is her performances for Hitchcock in this and in To Catch a Thief that will stick with me forever. Kelly may not be the most iconic of Hitchcock’s “cool blonde” aesthetic — that honor arguably belongs to Kim Novak in Vertigo — but her work as Lisa Fremont deserves to be in consideration. This is as undervalued and overlooked a performance as any she gave.

Rear Window is magnificent for a multitude of reasons. It has withstood the test of time, and no facet has lost an ounce of effectiveness. As a primer into Hitchcock’s vast, varied, and essential oeuvre, it is the perfect starting point. As an example of old Hollywood studio filmmaking at its finest, much like Kelly’s mesmerizing entrance, it does not get more unforgettable than this, that’s for darn sure.

Celebrating its 70th anniversary, Rear Window is available on DVD, Blu-ray, 4K Ultra HD, and can be purchased digitally on multiple platforms.