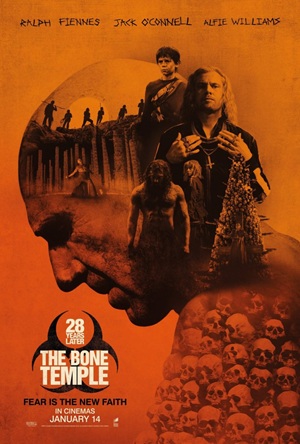

28 Years Later: The Bone Temple (2026)

by Sara Michelle Fetters - January 16th, 2026 - Movie Reviews

Heavy Metal Bone Temple is a Theologically Dense Thrill Ride into Life, Death, and Resurrection

While I’m not ready to say I liked 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple more than I did its magnificent predecessor, last summer’s 28 Years Later, I will state that director Nia DaCosta, writer Alex Garland, and producer Danny Boyle deliver one of the more ambitious, disturbing, thought-provoking, and all-around awesome sequels I’m likely to see in 2026 — and it’s only January. This masterfully calibrated entry in the 28 Days Later universe is an angelically abhorrent stunner, overflowing in astute, humanistic insights and socially prescient commentary that’s intermixed amid all the gruesome ultraviolence and skull-crushing intensity. Calling it unforgettable barely scratches the surface..

Soon after the events of the previous installment, young Spike (Alfie Williams) finds himself in the clutches of Sir Lord Jimmy Crystal (Jack O’Connell) and his seven malevolent, blonde-haired Fingers, all of whom are also named Jimmy. Spike must fight one-on-one with a Finger. If he kills his assailant, he’ll take that kid’s place, be renamed “Jimmy,” and get to look forward to a future of pillaging, marauding, and doing all sorts of irredeemable mischief at Sir Jimmy’s direction. Not exactly a happy ending.

But if he doesn’t? Death is death, and it’s probably better via the knife of a Finger than delivered by the blood-smeared teeth of one of the marauding infected that roam freely throughout the United Kingdom.

Meanwhile, Dr. Kelson (Ralph Fiennes) remains the custodian of his ossuary temple. During one of his outings to bring back carcasses so they may have a final resting place and not be left to rot, he again encounters the powerful alpha he has nicknamed “Samson” (Chi Lewis-Parry). After stunning him with a morphine dart, instead of killing the Rage Virus–infected behemoth, he treats the zombie’s wounds. There’s something different about Samson, a peculiarity that has Dr. Kelson wondering if there’s more going on behind the man’s eyes than a single-minded desire to rip off the heads of his victims and feast on their mutilated remains.

While this is still Spike’s coming-of-age story, this time he takes on the persona of an active observer, with the parallel plots revolving around Sir Jimmy and Dr. Kelson sliding into the spotlight. The former is a devout satanist, his world having shattered so completely in childhood that he now believes he is the son of the Devil himself, charged with giving humanity “charity” by ending lives and sending souls to Hell. There’s more peace there, after all, than amid the carnage of this zombie wasteland that’s been discarded by the remainder of the world to rot away out of sight (and out of mind).

Dr. Kelson is an atheist, but he also still believes in his Hippocratic oath. His relationship — friendship? — with Samson reignites something inside of him: a desire to not only ease the constant suffering of the infected but maybe even resume his experiments involving the Rage Virus itself. Dr. Kelson has no illusions that he’ll find a cure — not with his limited resources. But he may be able to give the infected back something they’ve been missing for almost three decades now: their free will.

There’s no question as to whether Sir Jimmy , his Fingers, and Dr. Kelson will all come into contact; the mystery is what will happen when they do. The entire film is designed to be one gory march that leads to that destination. But how it gets there, what happens when these polar opposites meet, and how this affects Spike and his evolving understanding of the world — that all comes as a surprise. There are no easy answers, and the debates over questions of existence, religion, and morality are fascinating in their penetrating, meditative specificity.

Although this universe remains grounded in the rules Garland and Boyle established in 28 Days Later (and reaffirmed with 28 Years Later), at no point did I feel like DaCosta was handicapped by that. This is a lushly vibrant sojourn into an apocalypse, with the colorfully vibrant, wide-screen cinematography crafted by Oscar nominee Sean Bobbitt (Judas and the Black Messiah) generating an immersive, almost dreamlike aura that gives the gut-wrenching terrors a painterly urgency that’s beauteously unsettling. Editor Jake Roberts (Hell or High Water) eschews the documentary-like verité style of the previous entries, allowing scenes to play out to their maximum intensity, no matter how repugnant or disturbing.

But it is how DaCosta handles the intricacies of Garland’s rich, multilayered screenplay that truly impressed me. She has an ability to make theological discussions come off authentically and not like some flowery back-and-forth by a talented, if pretentious, playwright. When O’Connell and Fiennes do get together, their relationship is nothing like I imagined it. DaCosta gives them the freedom to bounce off one another with a tentative, relatable vibrancy. Fear, happiness, curiosity, even joy — they experience it all. The pair travel along an uncertain road as they take careful steps toward a deeper understanding, each inspired by the other to continue their work for as long as they can, no matter the cost.

The performances are strong throughout, and there isn’t a weak link. While Fiennes and O’Connell are extraordinary, praise must also be given to Lewis-Parry as Samson and Erin Kellyman as the most menacing Finger, Jimmy Ink. I don’t want to say too much about either, as going into the intricacies of their characters does tread into spoiler territory. But both are superb, and neither plays it safe. These are rich portraits of fractured humanity starting to heal itself even when it didn’t know it needed to (or even how to go about it).

The seeds do get set for a third 28 Years Later entry in Garland and Boyle’s overarching tale. While this cliffhanger isn’t as jaw-dropping or as sudden as the last, I do imagine some viewers will feel unfulfilled. It’s a big tease, and I did hear a few muffled sighs when the screen went black and the familiar strains of a certain John Murphy theme wormed their way inside composer Hildur Guðnadóttir’s dynamically pugnacious score.

Not that it matters. The Bone Temple is phenomenal. Wild, weird, and overflowing in rich ideas, the film is a nasty soliloquy of birth, death, and resurrection that begins like some tragically austere Puccini operetta only to climax with death-metal majesty like it’s the most raucous Iron Maiden concert ever staged. Armageddon has rarely been this beautiful. Or this profound.

– Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 3½ (out of 4)