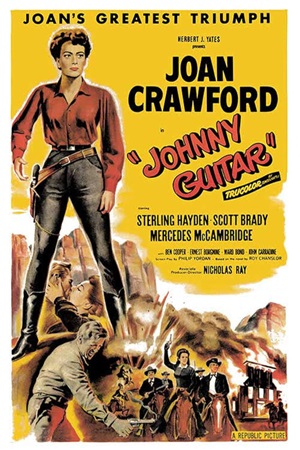

Unforgettables: Cinematic Milestones #32 – Johnny Guitar (1954)

by Sara Michelle Fetters - September 25th, 2024 - Features

Nicolas Ray’s queer-coded 1954 revisionist Western remains gloriously — and subversively — ahead of its time

NOTE: This feature originally appeared in the August 30, 2024 edition of the Seattle Gay News.

Is Johnny Guitar the most subversive major studio Western ever made? A pair of powerful women lording it over everyone else in the most masculine of Hollywood genres? Making the male lead — one of the most ruggedly macho stars of his generation — a lovestruck, browbeaten cuckold? The screen drowning in colorful, oversaturated subtext more akin to a Douglas Sirk melodrama than a gun-toting oater? Director Nicolas Ray‘s 1954 classic certainly checks all of those subversive boxes — and several more as it gallantly saunters to its expectedly bullet-riddled conclusion. It’s something special.

Yet precious few noticed any of this at on the film’s original release. Critics were largely indifferent, and some were even downright hostile. Domestic audiences shrugged at it and mostly stayed home. Hollywood industry dialogue about the picture generally focused on the supposed feud between stars Joan Crawford and Mercedes McCambridge, not the narrative ins and outs of the story.

European audiences were the first to notice there was far more going on with Johnny Guitar than met the eye. Before they became vaunted auteurs who helped birth the French New Wave, Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut were celebrated critics, and both bent over backward to heap praise on the bracingly daring Western. Martin Scorsese would later be a vocal champion for the picture as well, while Pedro Almodóvar devoted a memorable subplot in his 1988 classic Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown to celebrating Ray’s opus.

Heck, in 2008 Johnny Guitar was even selected for preservation for the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress, assuring it would be preserved forever. Not bad for a picture that legendary New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther pithily proclaimed was nothing more than a “flat walk-through — or occasional ride-through — of western clichés.”

I didn’t know any of this when I brought home a VHS copy from my local video store. It starred Joan Crawford and Sterling Hayden. It had a cool cover. I was going through a period of binging Western after Western, including the likes of Shane, The Searchers, and A Fistful of Dollars. I had no clue I was about to put on a campy, brazenly over-the-top smorgasbord of feminine excess and gender nonconformity. I could never imagine how much I’d wish I could emulate Crawford and McCambridge than I did the likes of Hayden, Ward Bond, and Ernest Borgnine. Suffice it to say, I was mesmerized.

Pondering it now, it’s impossible not to think this was all by design. As a result of how Ray and cinematographer Harry Stradling frame things, Crawford and McCambridge dominate the screen. The colors pop, but when shadows fall, it’s almost always in tandem with how one woman angrily — or maybe seductively? — glares at the other from across the wooden floor of a saloon or out in the wilds next to a raging creek. The men always linger sheepishly behind them, sometimes in oddly symmetrical configurations that wouldn’t have been out of place in a 1930s Hollywood musical like Footlight Parade, Dames, or 42nd Street.

I’m not sure if the plot, loosely based on the book by Roy Chanslor, even matters. On the outskirts of an Arizona cattle town lies a saloon owned by the larger-than-life Vienna (Crawford). It’s conveniently located near what will soon be a major railroad hub, and Vienna is a savvy enough businesswoman to know this will transform their tiny community into a bustling metropolis — and her business will be right at the center.

Complications arrive on several fronts. Emma Small (McCambridge) loathes Vienna, seemingly for stealing away the affections of the notorious Dancin’ Kid (Scott Brady), whom she purports to love, and she’ll stop at nothing to see the saloon owner booted out of town. Local cattle baron John McIvers (Bond) is against the railroad, and he’s also prone to do Emma’s bidding (even when he knows she’s wrong). Finally, there is the arrival of Johnny “Guitar” Logan (Hayden), a reformed gunslinger and Vienna’s former lover, who would like to reignite their previous affair.

Crawford and McCambridge may have hated one another in real life, but all the sparks that fly in the film are undeniably between their characters and — sorry, Mr. Hayden — absolutely no one else. Ray pointedly plays this dynamic up to the nth degree. He minimizes the men, relegating them and their issues to the background. He questions their masculinity. He showcases how these women are not just their equal in business and overall intelligence but also more violently determined to stand their ground.

If not for Johnny Guitar, it’s hard not to wonder if, genre-busting revisionist Westerns like One-Eyed Jacks (1961), The Shooting (1966), Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1968), McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971), The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), Unforgiven (1992), and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007) would even exist. Would LGBTQ+ Westerns like The Ballad of Little Joe (1993), Brokeback Mountain (2005), and The Power of the Dog (2012) have found funding to start production, let alone garner critical acclaim and win major industry awards?

I’m sure they probably would, but to say that Ray took a shotgun to the locks on the genre’s gatekeeping doors and showed other storytellers a path to craft something unique and different is also true. There’s a reason that, seven decades after its original release, audiences and filmmakers alike are still wowed by Johnny Guitar and all its colorfully ambitious histrionics. It enthusiastically disrupts the status quo: Vienna and Emma’s (deliberately?) Queer-coded conflict is an all-time blast of gun-toting mayhem and fiery theatricality that gleefully burns the conservative house down to its ashes. How’s that for unforgettable?

Celebrating its 70th anniversary, Johnny Guitar is available on DVD and Blu-ray, and can be purchased digitally on multiple platforms.