Ending at the beginning and the beginning of the end

NOTE: This feature originally appeared in the December 3, 2021 edition of the Seattle Gay News. It is reprinted here by permission of the publisher Angela Craigin.

Normally I don’t know where to begin. This time I haven’t the first clue where to end.

The problem is that there isn’t one. I began this series with certain ground rules, the most ironclad being that my cutoff would be my favorite film of 2020 — Nomadland — and I would not consider anything released from that point forward. It was the only way I could get this to work, as I didn’t want to be so taken with the “now” that I would forget to keep giving the “then” its due.

But almost a full year has passed since I started this endeavor, and goodness knows there are a small handful of films — like Shaka King’s Judas and the Black Messiah, Eliza Hittman’s Never Rarely Sometimes Always, Regina King’s One Night in Miami…,Michael Sarnoski’s Pig, Emma Seligam’s Shiva Baby and Julia Ducournau’s Titane — that I’d strongly consider adding to the list right this second. Time marches on, and new features are released each week. It’s a never-ending cycle, all of which makes finding a conclusion impossible.

My journey through over a century of film has also been a reexamination of my own four-plus decades of life. It has been a story filled with intimate remembrances, many of which I’ve never told to anyone before. Truth is, my obsessive love affair with cinema is tied to my self-acceptance of the adult I am today. They are forever linked, and that’s exactly how it should be.

So many flashbacks overwhelm my memories. They collide into one another, creating a mishmash of thoughts and feelings that are as extraordinary as they are jarring: Standing in line for eight hours to see The Empire Strikes Back with my parents. My dad convincing the usher at a small Spokane theater to let us stay for the next showing of Disney’s The Jungle Book by promising we’d buy another bucket of popcorn. Going to watch Hoosiers by myself four times over the course of a single weekend. My best friend Scott and me buying tickets to some random kiddie movie, only to sneak into a double feature of Die Hard and Alien Nation. Recently seeing Ran for the first time in a theater, sitting on the edge of my seat and grinning in wide-eyed glee.

That last one reminds me of something else. Out of all 1,001 motion pictures included here, it’s safe to say I’ve watched roughly half of them at home. While nothing can replicate the theatrical experience, a great film is a great film no matter how it is viewed. With the rise of streaming and any number of other ways people are now consuming visual media, this point remains true. Greatness will always rise to the occasion, and there is something magical in the discovery of a new favorite, no matter how it is viewed that first time.

Yet there is something about being in that auditorium, waiting for the lights to go out, sitting in excited anticipation of being wowed. This still happens for me each time I enter the theater. No matter what the occasion, no matter what the film, I will always climb into my seat, hoping for something magnificent. I want to be wowed. I long to be blown away.

Then there is the communal aspect. I remember watching Who Framed Roger Rabbit and the entire audience breaking out in spontaneous applause when Donald and Daffy Duck inexplicably took the screen together at dueling grand pianos. I still smile when I think about experiencing the Wizard of Oz during the Magic Lantern Theater’s annual summertime family film festival and listening to the adults happily singing along to “Follow the Yellow Brick Road.” I get happy shivers recollecting watching You’re Next with a raucous promo audience — the giant cheer that went up when a befuddled character looked at the woman he supposedly loved and stated, “Who knew you were so good at killing people?” is imprinted in my memory forever.

Not every communal experience is a good one, though. Cell phones ring. The new fancy seats recline and get adjusted almost as if the occupants are playing their own version of musical chairs. People act like they’re sitting in their living rooms on a couch folding laundry and not in a room with a cadre of strangers. Films are projected underlit. The sound is sometimes either set too loud or without all of the channels activated properly.

But those good experiences? They live forever. There’s a reason people love to watch those audience-reaction videos of Captain American lifting Mjölnir in Avengers: Endgame — and it’s also why tens of thousands cram into various sports stadiums to collectively cheer on their favorite teams. Humans like feeling things together. While we often hide who we are from the world, something is released during these moments, and as strong as the home viewing experience can be, this is still a thing that can never — will never — be replicated.

I feel like the finale of Peter Weir’s magnificent, ahead-of-its-time masterwork The Truman Show sums up this series much better than I ever could. From the time of his conception, Truman Burbank (Jim Carrey, in a career-best performance) has lived his life in front of billions of television viewers. Unbeknownst to him, his “god” is Christof (Ed Harris), the creator of his program, a mad storytelling magician who has designed a thriving faux coastal California community for his oblivious star to grow up in.

The crux of Andrew Niccol’s superlative script is Truman’s sudden awakening to the fiction his life has been constructed upon. He’s bursting at the seams trying to buck the conventionality that’s been thrust on his shoulders. His wife Meryl (Laura Linney) doesn’t love him. His best friend Marlon (Noah Emmerich) keeps steering him towards unadventurous pursuits. His mother (Holland Taylor) keeps trying to convince him to lower his expectations and not aspire to be greater than he is.

Whether intentional or not, Weir and Niccol have fashioned the ultimate Trans allegory. While Truman does not aspire to change his gender, by the sheer weight of community norms he’s still forced to keep his true self hidden. He must fight to break through that crippling façade. Even when Christof warns him that there will be heartbreak and that untold hardship will come his way if he exits the world that’s been meticulously crafted for him, Truman still opens the door to an indefinite tomorrow. It’s the only way he can survive.

My trek to being my authentic self has walked hand in hand with my love of cinema. I’m drawn to stories of identity, of individuals becoming their true selves by overcoming — and sometimes failing to overcome — obstacles that are frequently difficult to define. Art puts up a mirror to the reality we hold dear, offering up a window to see and analyze things in ways we otherwise might not have considered.

This list reveals more about me and my personality than it does anything else. I do not claim these 1,001 motion pictures are among the greatest ever made. I do contend that these are some of the best ones I have ever seen, and I’m thankful I’ve taken the time to watch every single one of them. Each film on this list has helped shape who I am today and has put me in touch with the person I still aspire to become tomorrow.

Like Truman Burbank, this list is a doorway. Going through it, newcomers will find ineffable wonders, some of which will be excruciating, others perplexing, and more than a few a little bit mystifying. But there will also be love. There will be excitement. There will be adventure and suspense and terror. There will be laughter and there will be tears. Each experience will be different, and no two opinions will ever be 100% the same.

At the conclusion of The Truman Show, Truman asks wistfully, “Was any of it real?” The answer? As Christof states, Truman was real, and that’s why people wanted to watch. That is art. It is also life. Reality is what we make it, and we find inspiration in the microcosms that make up each second of every hour of each day.

There is no end to this list, as it will continue to evolve with every new film I watch. I wouldn’t have it any other way.

The oldest film on the list this month is Georges Méliès’ groundbreaking, otherworldly 1902 classic A Trip to the Moon. The most recent is Studio Ghibli’s When Marnie Was There from 2014, directed by James Simone and Hiromasa Yonebayashi. Both play with time and perception in fascinating ways, and I’m continually amazed by their almost effortless storytelling originality.

A few statistics:

– Alfred Hitchcock has the most films on the list with 11, followed closely by John Ford with 10. Six other directors – Akira Kurosawa, Billy Wilder, Howard Hawks, Ingmar Bergman, John Huston and Peter Weir – have nine.

– Kathryn Bigelow is the female filmmaker with the most titles with four. A total of 61 women directed or co-directed at least one entry on the complete list.

– Satyajit Ray’s “The Apu Trilogy” (Pather Panchali, Aparajito, The World of Apu) is the only trilogy where every title makes the cut.

– I’d stated upfront this list likely skewed a little toward the 1980s, and this is borne out: 1988 has the most entries, with 25 titles, followed closely by 1982 with 23 and both 1985 and 1987 with 22 each. Other notable years include 1974 and 1999, both with 19 titles, 1959 with 17, and 1969 with 16. Widely considered to be the greatest year in cinema history, 1939 came in with only 15 titles on my list, which surprised me.

– The decades with the most representatives are the 1970s with 132 total entries, the 1980s, with a whopping 183 and the 1990s with 143.

– There are only 17 silent films on the list, making this a rather large blind spot I need to start to address.

– The titles I’ve watched the most times on the list: 2001: A Space Odyssey, Casablanca, Dragonslayer, Halloween, His Girl Friday, Hoosiers, Jaws, Star Wars, The Thing and Working Girl. Can’t tell you precisely how many times I’ve watched all of those, but I know it’s enough that I can pretty much recite each film’s dialogue word-for-word.

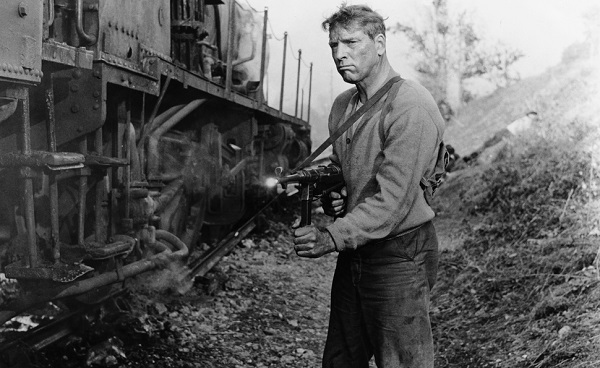

The Train (John Frankenheimer) (1964)

Trainspotting (Danny Boyle) (1996)

Treasure Island (Victor Fleming) (1934)

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (John Huston) (1948)

The Tree of Life (Terrence Malick) (2011)

The Tree of Wooden Clogs (Ermanno Olmi) (1978)

Tremors (Ron Underwood) (1990)

A Trip to the Moon (Georges Méliès) (1902)

The Triplets of Belleville (Sylvain Chomet) (2003)

True Stories (David Byrne) (1986)

The Truman Show (Peter Weir) (1998)

Tucker: The Man and His Dream (Francis Ford Coppola) (1988)

Two for the Road (Stanley Donen) (1967)

Two Women (Vittorio De Sica) (1960)

Ugetsu (Kenji Mizoguchi) (1953)

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (Jacques Demy (1964)

Under the Skin (Jonathan Glazer) (2013)

Underground (Emir Kusturica) (1995)

Underworld U.S.A. (Samuel Fuller) (1961)

Unforgiven (Clint Eastwood) (1992)

The Uninvited (Lewis Allen) (1944)

United 93 (Paul Greengrass) (2006)

An Unmarried Woman (Paul Mazursky) (1978)

The Untouchables (Brian De Palma) (1987)

Used Cars (Robert Zemeckis) (1980)

Vagabond (Agnès Varda) (1985)

Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (Jaromil Jires) (1970)

Vampyr (Carl Theodor Dreyer) (1932)

The Vanishing (George Sluizer) (1988)

Veronika Voss (Rainer Werner Fassbinder) (1982)

Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock) (1958)

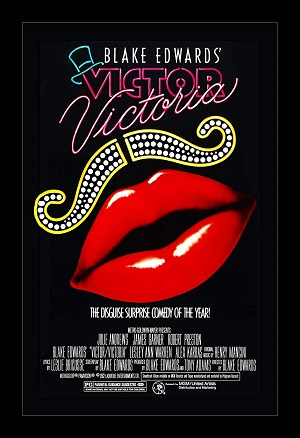

Victor/Victoria (Blake Edwards) (1982)

Village of the Damned (Wolf Rilla) (1960)

The Virgin Spring (Ingmar Bergman) (1960)

The Virgin Suicides (Sofia Coppola) (1999)

Viva Maria! (Louis Malle) (1965)

Volver (Pedro Almodóvar) (2006)

The Wages of Fear (Henri-Georges Clouzot) (1953)

Walkabout (Peter Weir) (1971)

Wall-E (Andrew Stanton) (2008)

Wanda (Barbara Loden) (1970)

The War of the Roses (Danny DeVito) (1989)

The War of the Worlds (Byron Haskin) (1953)

Watership Down (Martin Rosen) (1978)

The Wedding Banquet (Ang Lee) (1993)

Wendy and Lucy (Kelly Reichardt) (2008)

Westworld (Michael Crichton) (1973)

Whale Rider (Nikki Caro) (2002)

What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (Robert Aldrich) (1962)

What’s Eating Gilbert Grape (Lasse Hallström) (1993)

Wheels on Meals (Samo Hung) (1984)

When Harry Met Sally… (Rob Reiner) (1989)

When Marnie Was There (James Simone, Hiromasa Yonebayashi) (2014)

White Heat (Raoul Walsh) (1949)

The White Ribbon (Michael Haneke) (2009)

Who Framed Roger Rabbit (Robert Zemeckis) (1988)

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (Mike Nichols) (1966)

The Wicker Man (Robin Hardy) (1973)

The Wild Bunch (Sam Peckinpah) (1969)

Wild Strawberries (Ingmar Bergman) (1957)

Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory (Mel Stuart) (1971)

Winchester ’73 (Anthony Mann) (1950)

The Wind (Victor Sjöström) (1928)

The Wind Will Carry Us (Abbas Kiarostami) (1999)

Wings (William A. Wellman) (1927)

Wings of Desire (Wim Wenders) (1987)

Winter’s Bone (Debra Granik) (2010)

The Witches (Nicolas Roeg) (1990)

Witness (Peter Weir) (1985)

Witness for the Prosecution (Billy Wilder) (1957)

The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming) (1939)

The Wolf Man (George Waggner) (1941)

Woman in the Dunes (Hiroshi Teshigahara) (1964)

A Woman Under the Influence (John Cassavetes) (1974)

The Women (George Cukor) (1939)

Women in Love (Ken Russell) (1969)

Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (Pedro Almodóvar) (1988)

Wonder Boys (Curtis Hanson) (2000)

Woodstock (Michael Wadleigh) (1970)

Working Girl (Mike Nichols) (1988)

The World of Apu (Satyajit Ray) (1959)

Written on the Wind (Douglas Sirk) (1956)

Wuthering Heights (William Wyler) (1939)

Wuthering Heights (Andrea Arnold (2011)

Y Tu Mamá También (Alfonso Cuarón) (2001)

Yankee Doodle Dandy (Michael Curtiz) (1942)

The Year of Living Dangerously (Peter Weir) (1982)

Yi Yi: A One and a Two (Edward Yang) (2000)

Yojimbo (Akira Kurosawa) (1961)

You Can’t Take It with You (Frank Capra) (1938)

Young Frankenstein (Mel Brooks) (1974)

The Young Girls of Rochefort (Jacques Demy) (1967)

Young Mr. Lincoln (John Ford) (1939)

You’re Next (Adam Wingard) (2011)

Z (Costa-Gavras) (1969)

Zabriskie Point (Michelangelo Antonioni) (1970)

Zazie dans le Métro (Louis Malle) (1960)

Zero Dark Thirty (Kathryn Bigelow) (2012)

Zodiac (David Fincher) (2007)

Zombie (Lucio Fulci) (1979)

Zulu (Cy Endfield) (1964)

– This feature reprinted courtesy of the SGN