From Orlando to Perks of Being a Wallflower, the journey to self-acceptance remains a wild ride

NOTE: This feature originally appeared in the September 3, 2021 edition of the Seattle Gay News. It is reprinted here by permission of the publisher Angela Craigin. Part Eight of this series will appear in Friday’s edition (October 1, 2021) of the newspaper and online. It will be reprinted here at Moviefreak.com on November 3, 2021.

The summer before I started seventh grade I decided to switch from cross-country to football. There were reasons for this, chief amongst them being how I’d noticed how many kids were getting belittled for participating in such a “sissy” sport.

To be honest, this was not my experience. By the time I reached sixth grade I was 6’2” and a star basketball and baseball player. Heck, I was already attending summer basketball camp at one of the local high schools, even though technically I was too young. Not to toot my own horn, but from an athletic standpoint, I had a lot of credibility with my peers, and there weren’t many classmates who were going to make fun of me.

But I knew things they didn’t. This was the summer during which I started to grapple with my gender identity. I knew something was up; I just wasn’t entirely certain entirely what that was. I’m not saying I “borrowed” a dress or two from one of my friends who lived down the street. I will say is that if she ever wondered what happened to them and had looked through a box hidden in the recesses of my closet, I would have been in serious trouble.

Football was the perfect way to prove to myself — and hopefully to others — that there wasn’t a single thing feminine about me. It was a way to hide in plain sight, showcasing my abilities in what was considered the most masculine of sports. No one could make fun of or question me if I were a star on the gridiron, right?

Wrong.

Roughly three weeks into practice and on the eve of our first game, while I had solidified a starting spot at tight end, there were still certain things about my personality and the way I comported myself I hadn’t learned to conceal. We were standing in a huddle and the coach was giving this big speech about how we were all men now, that by being a part of this team, we’d left our boyhood behind, when all of a sudden, a longtime friend piped up out of the blue, “Well, that’s great, coach, but if that’s the case, someone needs to tell Fetters to stop standing in the huddle like a girl.”

That was it. Just a tossed-off statement meant to elicit laughs, a joke I chortled right along with. But inside? Inside I was ruined, and from that point forward I made it a mission to eradicate every last ounce of femininity I may have however inadvertently been displaying. How I walked. How I talked. How I held my books. My haircut. All of it. It had to be erased.

By 1991 I was writing reviews for The Spokesman-Review as part of its “Our Generation” teen section. I’d spent the summer waxing poetic about all of the big Hollywood releases, including Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, Terminator 2: Judgment Day, Point Break, City Slickers and The Rocketeer, while also peppering in smaller art house fare whenever I could.

One film I did not review was Jennie Livingston’s now-classic documentary Paris Is Burning. It was the first time I watched something and immediately knew I could not talk about it. I was too close to the material, and I worried that if I’d written anything about the film people would immediately know everything I was suppressing.

Not that I felt like I was a part of the world Livingston so lovingly and intimately documented. I knew I wasn’t a drag queen. I knew I didn’t want to parade myself around in that manner, strutting across the stage like a supermodel in total control of my environment. But I felt these stories so personally; these internalized struggles for acceptance and authenticity were all ones I held instant kinship with. It was too much for me, and other than placing the film on my year-end top ten list, I stayed mum on why I felt they were magnificent.

A couple of years later, I was a student at the University of Washington. I was no longer a top athlete. I wasn’t a big fish in a small pond. It was just me and my studies and not too much more than that. Then I stopped going to class. I found every excuse not to study. I was self-sabotaging in just about every way I could, and if not for the friendships I’d made — ones that have lasted until today — I somewhat doubt I’d still be here.

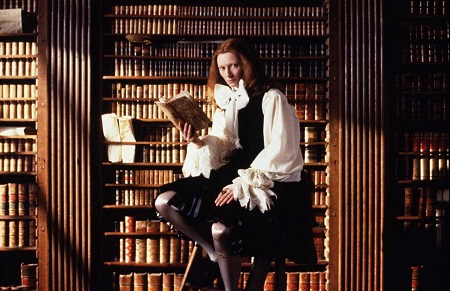

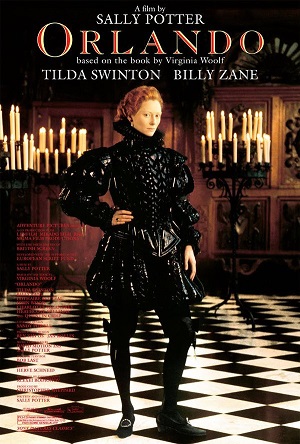

During this time, I went to the Varsity Theater to watch Sally Potter’s exquisite Orlando. Virginia Woolf is one of my favorite writers, so I was already familiar with this story of a young nobleman commanded by Queen Elizabeth I to never grow old, who finds himself transforming into a woman as the centuries quietly pass.

But I never felt as connected to the tale as I did sitting in that darkened auditorium. Tilda Swinton’s performance blew my mind, and the way Potter found ways to make the material come alive in so many imaginative ways took me entirely by surprise. The inner truths residing inside the subtext of the narrative shook me to my core, forcing a look back at my recent history that was as necessary as it was difficult.

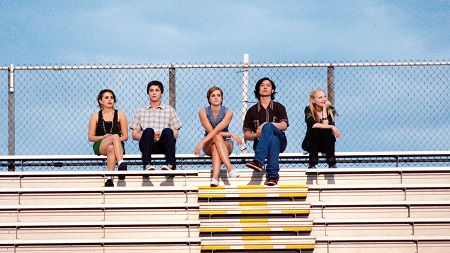

Stephen Chbosky’s 2012 adaptation of his best-selling novel The Perks of Being a Wallflower wrecked me for several reasons, chief among them how it allowed all of those seventh-grade memories to come flooding back. Set in the 1990s — when I was in high school — the story revolves around an introspective freshman named Charlie (Logan Lerman), who aspires to be a writer. He makes friends with a pair of free-spirited seniors, Patrick (Ezra Miller) and Sam (Emma Watson), who take the youngster under their wing and impart some of what they’ve learned during the past four years of school.

This is a rare instance where I’d say book and film come astonishingly close to being equal. Chbosky taps into what it is like to live under a constant shadow, understanding how kids can conceal important aspects of themselves to fit in with their peers. Or, if that’s not possible, to fly under the radar just well enough that it’s unlikely they’ll get picked on, as those interested in bullying would be likely to go after more obvious targets instead.

It’s not altogether shocking that I could relate to a lot of this. While I never considered myself Gay, I still understood Patrick’s zeal to be true to himself, yet not so much that he could end up ostracized, beaten up, or worse. I could come up with valid reasons for shaving my legs — e.g., skin conditions, muscle injuries, etc. — but I wasn’t about to push things further than that. It was about hiding in plain sight, and in that way Patrick and I had a great deal in common.

I could see myself in so many characters, though, and not just Charlie, Patrick and Sam. Most notably was Mary Elizabeth, so beautifully portrayed by Mae Whitman. Her reckless fearlessness masked a needy timidity that she refused to let others see. I admired the way she said what she thought and was so open with her feelings, yet at the same time held back, so as to maintain an aura of mystery she hoped others would both want to see through yet still be unable to pierce. I related to all of that, and I sort of felt like Chbosky had secretly videotaped my own high school years and based this character implicitly on what he filmed.

Paris Is Burning, Orlando and The Perks of Being a Wallflower were not the only times I felt like I could see facets of who I am up on the screen. This list is littered with such experiences, some of which I’ve already spoken about in detail in previous chapters of this ongoing expedition.

What connects this trio is how each looks at how all of us, whoever we are, conceal parts of ourselves from the world and the reasons why we do so. They analyze the degrees of fear and insecurity that lead so many to make drastic, often detrimental decisions that have lasting implications on the rest of their lives. They do so with empathy and grace, ultimately showcasing a powerful resilience to boldly be ourselves, no matter what the cost, that every viewer should hopefully want to aspire to.

While I wish I could have had that realization back in seventh grade, it’s clear my saga of self-discovery would not have led me here had that been the case. Regret is natural. So is wondering aloud about shouldas, wouldas and couldas. But the experiences of my life are uniquely mine, and I’m happy I’ve learned to embrace them. The journey to self-acceptance is a pretty wild ride, and I wouldn’t have had it any other way.

The oldest movie on the list this month is 1921’s surrealistic New Year’s Eve marvel The Phantom Carriage. This impressionistic stunner from Swedish director Victor Sjöström might be one of the most influential silent films ever made, so it’s a pity that far too few know anything about it.

The newest title is the 2020 release I mentioned back in the first entry of this series, Chloé Zhao’s Academy Award winner for Best Picture, Nomadland. Having now watched this one a couple more times over the past year, I’ve come to love it even more. I get lost inside this drama’s windswept magnificence that’s impossible to resist, this haunting aria of dreams dreamt and loners making lasting connections on a not-so-lonely highway.

And what are the films about childhood or transformative friendships that rest nearest your heart? My list of favorites is a long and glorious one, and I’m certain yours are as well.

My Twentieth Century (Ildikó Enyedi) (1989)

Naked (Mike Leigh) (1993)

The Naked Kiss (Samuel Fuller) (1964)

The Naked Spur (Anthony Mann) (1953)

The Narrow Margin (Richard Fleischer) (1952)

Nashville (Robert Altman) (1975)

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (Hayao Miyazaki) (1984)

Near Dark (Kathryn Bigelow) (1987)

Network (Sidney Lumet) (1976)

Never Cry Wolf (Carroll Ballard) (1983)

A New Leaf (Elaine May) (1971)

Night and the City (Jules Dassin) (1950)

A Night at the Opera (Sam Wood) (1935)

Night Moves (Arthur Penn) (1975)

Night of the Demon (Jacques Tourneur) (1957)

The Night of the Hunter (Charles Laughton) (1955)

Night of the Living Dead (George Romero) (1968)

The Night Porter (Liliana Cavani) (1974)

A Night to Remember (Roy Ward Baker) (1958)

The Nightingale (Jennifer Kent) (2018)

A Nightmare on Elm Street (Wes Craven) (1984)

Nights of Cabiria (Federico Fellini) (1957)

Ninotchka (Ernst Lubitsch) (1939)

Nomadland (Chloé Zhao) (2020)

North by Northwest (Alfred Hitchcock) (1959)

Nosferatu (F.W. Murnau) (1922)

Notorious (Alfred Hitchcock) (1946)

Now, Voyager (Irving Rapper) (1942)

The Official Story (Luis Puenzo) (1985)

Old Acquaintance (Vincent Sherman) (1943)

The Old Dark House (James Whale) (1932)

Old Yeller (Robert Stevenson) (1957)

On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (Peter Hunt) (1969)

On the Waterfront (Elia Kazan) (1954)

Once (John Carney) (2007)

Once Upon a Time in America (Sergio Leone) (1984)

Once Upon a Time in China (Tsui Hark) (1991)

Once Upon a Time in the West (Sergio Leone) (1968)

One False Move (Carl Franklin) (1992)

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (Milos Forman) (1975)

One Sings, the Other Doesn’t (Agnès Varda) (1977)

Onibaba (Kaneto Shindô) (1964)

Only Angels Have Wings (Howard Hawks) (1939)

Operation Petticoat (Blake Edwards) (1959)

Ordet (Carl Theodor Dreyer) (1955)

Orlando (Sally Potter) (1992)

Our Man in Havana (Carol Reed) (1959)

Out of Sight (Steven Soderbergh) (1998)

Out of the Past (Jacques Tourneur) (1947)

The Ox-Bow Incident (William A. Wellman) (1942)

Paddington 2 (Paul King) (2017)

The Palm Beach Story (Preston Sturges) (1942)

Panic in the Streets (Elia Kazan) (1950)

Pan’s Labyrinth (Guillermo del Toro) (2006)

Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills (Joe Berlinger, Bruce Sinofsky) (1996)

The Parallax View (Alan J. Pakula) (1974)

Parasite (Bong Joon Ho) (2019)

Pariah (Dee Reese) (2011)

Paris Is Burning (Jennie Livingston) (1990)

Paris, Texas (Wim Wenders) (1984)

The Passion of Joan of Arc (Carl Theodor Dreyer) (1928)

Pather Panchali (Satyajit Ray) (1955)

Pathfinder (Nils Gaup) (1987)

Paths of Glory (Stanley Kubrick) (1957)

Patton (Franklin J. Schaffner) (1970)

Pauline at the Beach (Éric Rohmer) (1983)

Peeping Tom (Michael Powell) (1960)

Pelle the Conqueror (Bille August) (1987)

People on Sunday (Robert Siodmak, Edgar G. Ulmer) (1930)

The Perks of Being a Wallflower (Stephen Chbosky) (2012)

Persona (Ingmar Bergman) (1966)

The Phantom Carriage (Victor Sjöström) (1921)

The Philadelphia Story (George Cukor) (1940)

Phoenix (Christian Petzold) (2014)

The Piano (Jane Campion) (1993)

Pickpocket (Robert Bresson) (1959)

Pickup on South Street (Samuel Fuller) (1953)

Picnic at Hanging Rock (Peter Weir) (1975)

Pierrot le Fou (Jean-Luc Godard) (1965)

Pillow Talk (Michael Gordon) (1959)

Pink Flamingos (John Waters) (1972)

Pinocchio (multiple directors) (1940)

Piranha (Joe Dante) (1978)

The Pirate (Vincente Minnelli) (1948)

Pixotte (Hector Babenco) (1981)

Planet of the Apes (Franklin J. Schaffner) (1968)

Planet of the Vampires (Mario Bava) (1965)

Platoon (Oliver Stone) (1986)

The Player (Robert Altman) (1992)

PlayTime (Jacques Tati) (1967)

Point Blank (John Boorman) (1967)

Police Story 3: Supercop (Stanley Tong) (1992)

Poltergeist (Tobe Hooper) (1982)

Portrait of a Lady on Fire (Céline Sciamma) (2019)

The Postman Always Rings Twice (Tay Garnett) (1946)

The Prestige (Christopher Nolan) (2006)

Pretty Baby (Louis Malle) (1978)

Prick Up Your Ears (Stephen Frears) (1987)

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (Ronald Neame) (1969)

Prince of Darkness (John Carpenter) (1987)

– This feature reprinted courtesy of the SGN